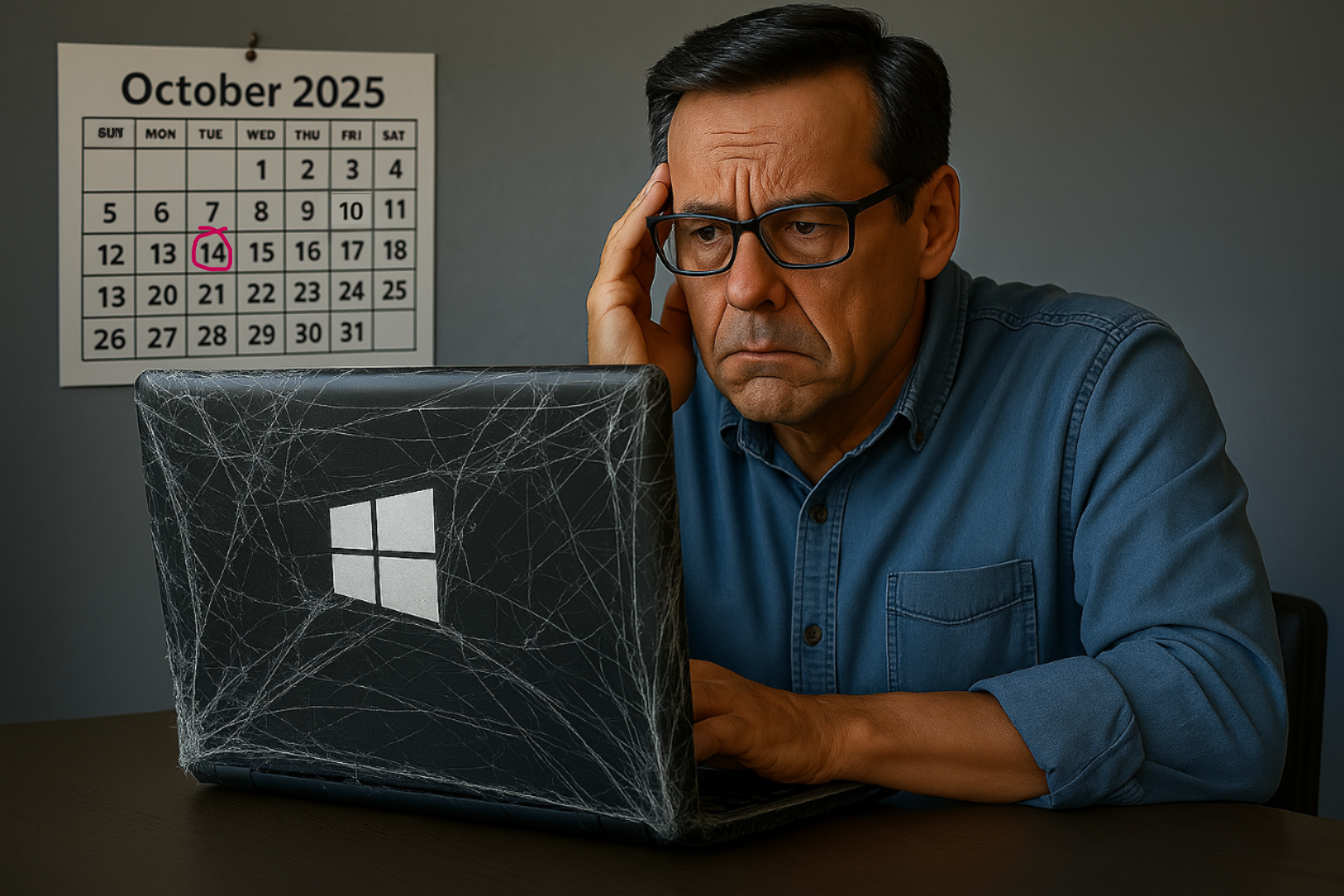

As was mentioned in a previous tip – #64: Tick, Tock, Time is up (nearly) for Windows 10 – this October sees Windows 10 take a last gasp as it slips beneath the waves. It hasn’t been getting any enhancements or fixes for a while, except for flaws which compromise its security. After October, it won’t even get any of those.

Well, not entirely. For $30 – for one year and then, who knows – extended support will be available for individuals, or a bit more if you’re a commercial operation, via the Extended Security Updates (ESU) program. Enrolment is not yet open but will be sometime before October 14th.

Microsoft has been signalling for a while now that everyone should move to Windows 11, but due to some somewhat particular (and to some, peculiar) hardware requirements for Win11, there are lots of otherwise perfectly workable Win10 machines which cannot be upgraded. More than half of all PC users will – unless they ditch their old machines and move beforehand – be on the wrong side of the line.

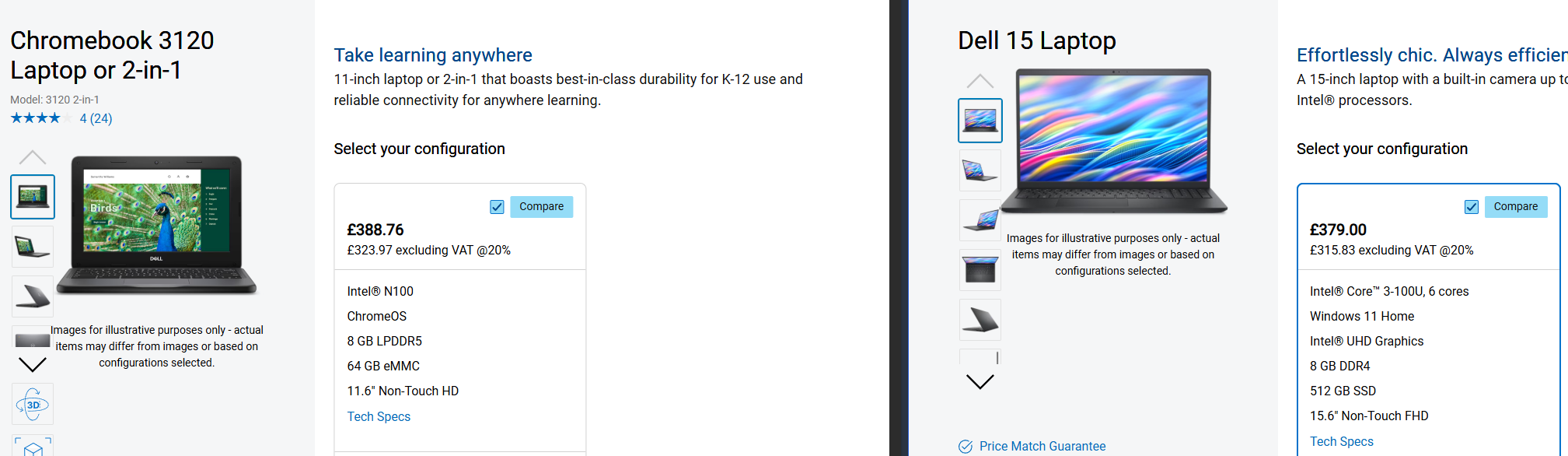

Hardware Upgrade Opportunity

Naturally, PC makers are leaning in on this forcing function; “oh dear, all your old PCs won’t be upgradeable so you’ll need to replace them all”. There are some pretty good reasons why Windows 11 has enforced a specific set of hardware specs, though: almost all to do with security. As threats evolve, modern hardware and operating systems have to develop means to counter them – and in the case of Windows 11, that requires a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0 chip to securely store information used to encrypt and protect the machine. Modern CPUs also need to be used, and even if a 7-year old Windows 10 PC might have a fast-enough processor and plenty of memory, it likely won’t have cutting-edge hardware to ensure it can stay secure.

Ever-engaging ex-Microsoft developer Dave Plummer has a good explainer on his Dave’s Garage channel.

Silicon Landfill

Even if you could add a TPM 2.0 module, lots of modern PCs won’t have a processor be on the allow list. One of the earliest flagship devices to fall into this trap is the Microsoft Surface Book, itself only 10 years old in October and although it has TPM 2.0, its CPU processor family is too limited.

The fear is that many users will (be forced to?) carry on running Windows 10 – just as lots still used Windows XP years after it was out of support – or they will grasp the nettle, upgrade to new hardware and then just junk their old machine?

Microsoft, for all its intent to be carbon neutral, is seen by some as an enabler for a likely surge in usable electronics being prematurely scrapped. It’s reckoned 240 million PCs will be ditched, and since the e-waste recycling rate is only around 25%, that’s the equivalent of 180m PCs going into landfill. If they were all laptops stacked on top of one another, it would be more than 10 times the height of the path of the International Space Station.

The flipside is that modern PCs are more energy efficient, they will be more productive (even just because they’re clean and fresh and not full of old stuff). People used to upgrade much more often, so if you only replacing a PC every 7-10 years then it’s better than it was 20 or 30 years ago, where they might only have lasted 4 or 5 years.

Another way

f you have a 10-year old laptop that hasn’t yet devoured its battery or caused incendiary problems, it might still be useful as a second machine or a hand-me-down to other family members.

A Surface Book with bulging battery – from The Microsoft Surface Swollen Battery Problem

One way to keep things running is to check out of the Windows ecosystem altogether.

Since there are over 1 billion users of Windows 10, lots of bad people will be trying to exploit them. Any vulnerability that is discovered in Windows 10 in future could be attacked by nefarious sorts, and since Microsoft won’t be patching it, then you’re at risk of having the crown jewels taken. Even if other operating systems that could run on the same hardware might be intrinsically less secure, they won’t be attacked as much if they are in the minority, so switching to something more obscure could be one form of avoiding attack.

You could wipe Windows and move it to Linux, maybe? Years ago, it might have been the path taken by the less mainstream user, and fans said every year was going to be “the year” of the Linux desktop.

If you’ve a PC – desk or laptop – which is beyond upgrading to Win11 and will be otherwise junked, it might be worth having a play. You could set the machine up to dual-boot between Windows and Linux, and that way could try using Linux and even switch to it as default – leaving Windows there “just in case”, even if it’s not supported and potentially at greater risk from attack.

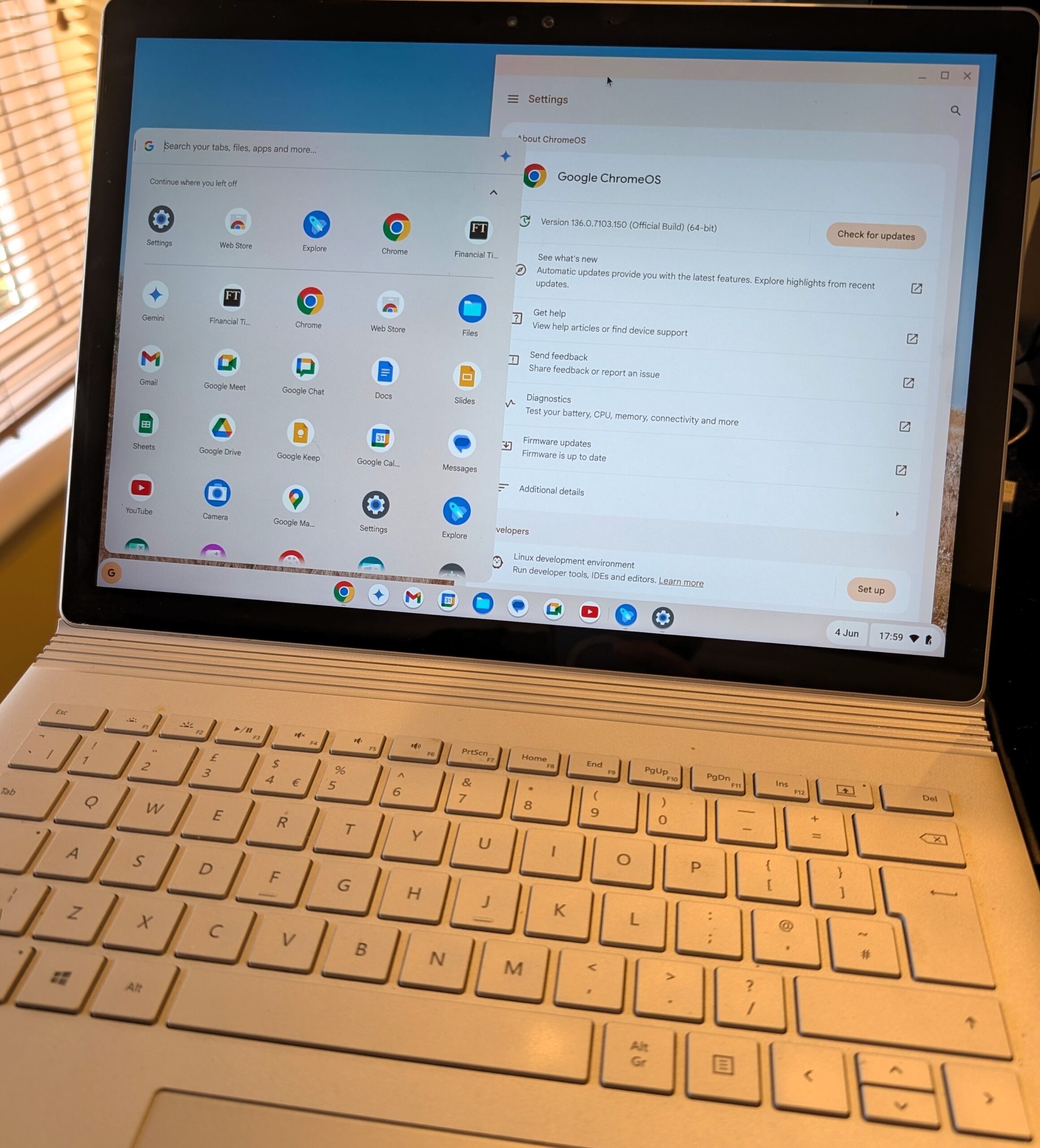

Chrome Up

A further idea, if you’re sure you don’t need the old machine and are prepared to wipe its Windows clean, is to have a play with Google’s ChromeOS. Designed originally for ChromeBooks – supposedly cheaper laptops that could run more efficiently on lower-spec hardware because they’re not encumbered with all the bloat of Windows – it’s actually possible to run ChromeOS in other places too.

Take a non-supported bit of kit – a first-gen Surface Book, for example – and it’s pretty easy to get the “ChromeOS Flex” variant up and running on it.

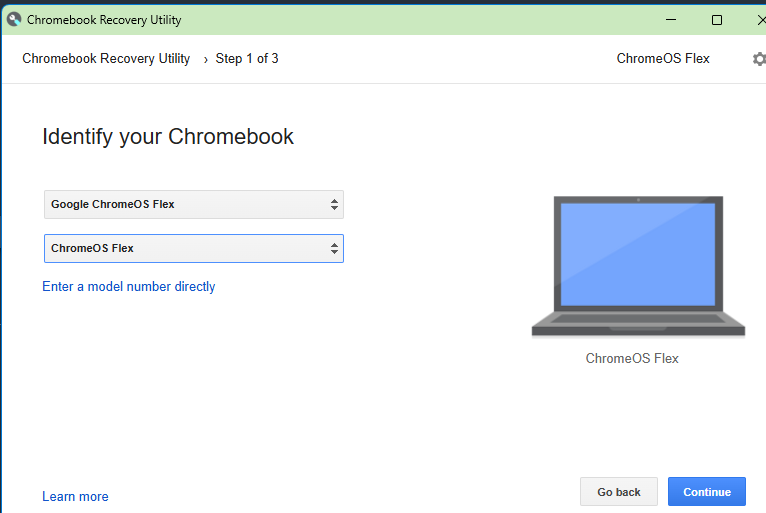

· Go to Prepare for installation – ChromeOS Flex Help for instructions. Start by installing the ChromeOS Recovery Utility browser addon on a working PC.

· Take a 16GB USB stick or memory card, and prepare it for ChromeOS by running the Chromebook recovery process, but instead of choosing an existing ChromeBook type, tell it you want to use a device called “Google ChromeOS Flex”.

· Once that’s done, restart your target PC with the bootable USB inserted – hold the SHIFT key while clicking on the Power / Restart option, or look for Advanced Startup options in the settings menu.

· You’ll be able to choose if you want to play with ChromeOS Flex by running it off the USB drive, or whether you’d like to wipe the disk on the PC and install it there instead. Choose.

In a surprisingly short amount of time, you’ll be able to walk through some self-explanatory setup procedures. Now to figure out what to actually do with the thing…

There are some gotchas with ChromeOS Flex – it doesn’t have the Google Play store and Android apps cannot be installed, though there are a variety of non-sanctioned ways to install a generic ChromeOS build (which does have Google Play etc). Good luck.