Following on from last month’s missive (#783) on internal competition, we’re going to look at a case where it may have successfully spurred a company, and an example of surprising collaboration between erstwhile competitors.

Also, how is it 33 years since R.E.M. released AFTP?

The world’s first automatic chronograph watch

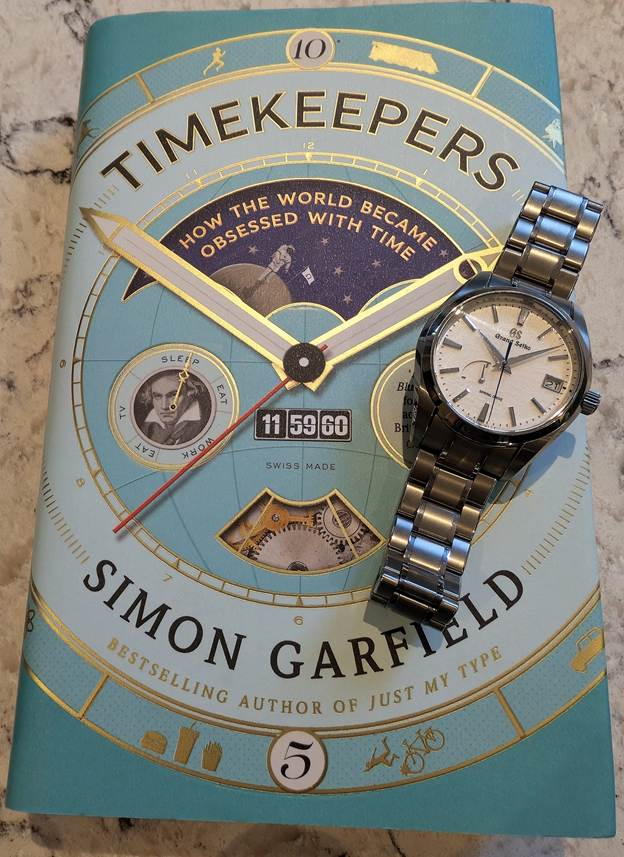

In the 1950s and 60s, clock and watch making was a hotbed of innovation just like the automobile industry and the race for space. New designs and technologies were coming thick and fast. Quartz crystals and batteries were still way out on the horizon, so the Swiss-dominated mechanical watch industry took great pride in building very precise instruments.

Open the back of a mechanical wristwatch and you’ll see many tiny components meshed together to make a little engine that measures out time and moves the hands on the dial appropriately.

Everything is generally driven by a coiled spring which is tightened and powers the whole “movement” as it unwinds in a controlled fashion. Manually-wound watches usually need a few turns of the “crown” on the side, perhaps every day or two. Many clocks work the same way, but with a larger spring might only need a few minutes of winding with a key every month or so.

Though pioneered in the late 18th century, automatic watches (which wind the spring through harvesting energy from the movement of the watch on the wrist) really took off in the early part of the 20th century. If you can see the movement of an automatic watch – either through the see-through “exhibition case” sometimes fitted, or by taking the back off it – it will often have a large “rotor” which swings back and forth as you move the watch on your wrist. You might feel or even hear it moving.

The rotor signifies that the dreadfully tiresome task of winding your watch every day was dispensed with. But some fancier watches with additional “complications” still had to be manually-wound; perhaps most notably chronographs, watches equipped with a stopwatch function.

Early “chronograph” clocks and watches were so called because they recorded the time using ink on the actual dial – making an ink mark or arc to record how long an event (like a horse race) lasted.

Necessity is the mother of invention

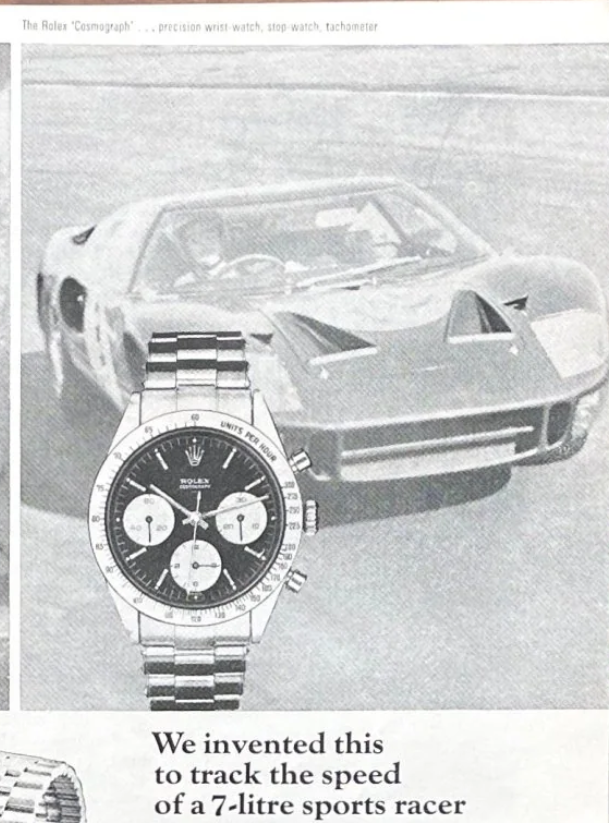

Wrist-worn chronographs (which only show the time, not write it) were popular in the 50s and 60s, especially amongst sporting types, perhaps inspired by famous racing drivers like Stirling Moss, Jim Clark or Dan Gurney.

Go-faster watch companies even named their products like Speedmaster, Daytona (after the Floridian racing circuit) or Carrera (after the Carrera Panamericana race).

But all of these famous chronographs were manually-wound. There was clear demand for the thrusting racy gentleman to have a stopwatch on his wrist that wound itself. Unfortunately, the technical challenge of building such a complicated mechanism that was small and robust enough to wear comfortably was tough.

It was common for watch makers to buy-in the movement they fitted to their watch, just as they’d have the dial made by a specialist, the case fabricated by another and so on. Think of it like a boutique car maker producing a vehicle using an off-the-shelf engine from an external manufacturer. Even major watch producers at the time, bought watch movements from “ébauche manufactures” like Valjoux, Lemania or Venus, none of whom had the resources to dedicate to producing an automatic chronograph. The famous Paul Newman Daytona – auctioned for $15M+ – had a manual-wind Valjoux 72 movement.

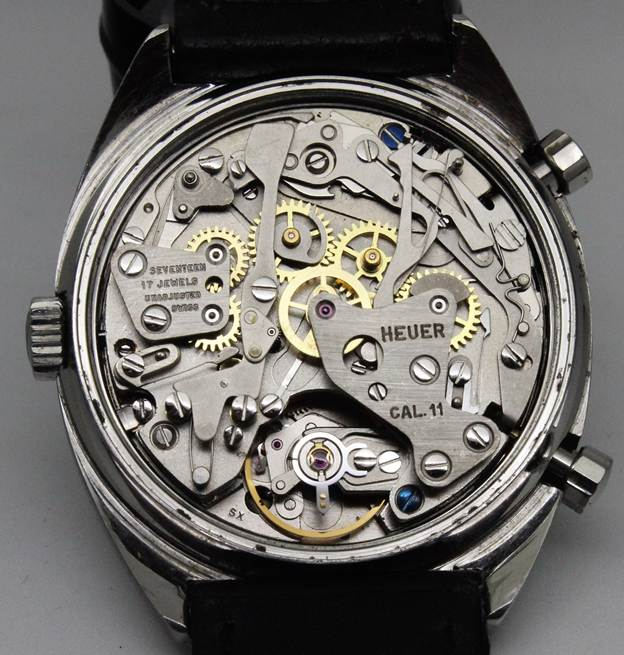

So began a famous collaboration between companies that might otherwise be seen as competitors – the watchmakers Breitling, Buren, Hamilton and Heuer got together with Dépraz, who made components for movements, to form what is now known as the Chronomatic Consortium.

Buren had pioneered their own automatic movements which had a “micro-rotor” rather than a big plate half the diameter of the watch. Dépraz had a chronograph module which they figured could be adapted to essentially bolt on to a variant of Buren’s base movement, thus giving them essentially two mechanisms powered by the same spring. In order for them all to fit together, the crown for setting the time had to be on the opposite side to the pushers that worked the chronograph.

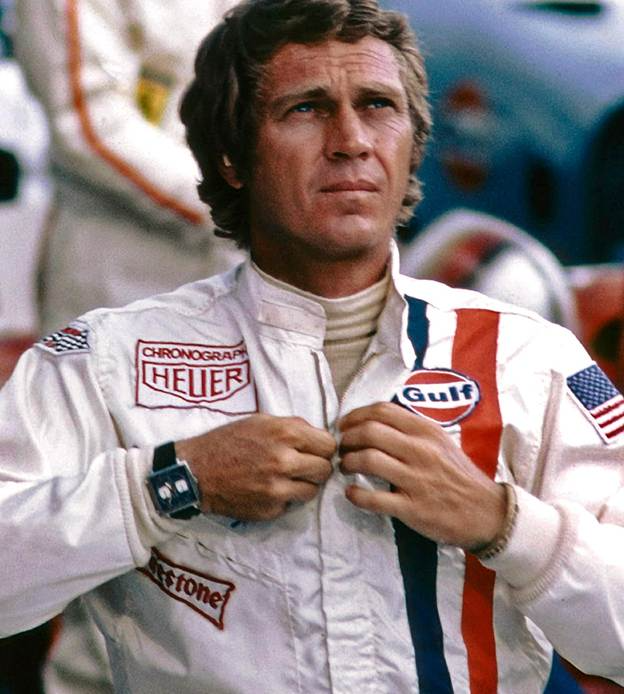

In 1969, Breitling, Heuer and Hamilton (who absorbed Buren during the years of development in the late 1960s) went on to launch ostensibly similar watches with the same basic “Caliber 11” movement within. Heuer’s are arguably most iconic, with the square-cased Monaco appearing on the wrist of the King of Cool, Steve McQueen, in the 1971 film, Le Mans.

The story behind McQueen’s watch is quite fortuitous; Heuer had a name for sports timekeeping and sponsored various cars and race teams. When McQueen was preparing for the Le Mans film, he said he wanted to look exactly like pro driver Jo Siffert, so donned the same overalls with the big Heuer logo. They also supplied props for the filming including watches.

Heuer and the rest of the “Project 99” / Chronomatic group touted their watches as the world’s first automatic chronographs, though competitor Zenith had been working on their own in-house movement and were so confident they would be first, they launched it in a watch brazenly called “El Primero”.

Even though they’d been working on it for 8 years, and announced it in January 1969, it took Zenith until September ‘69 to start selling their watch, by which time they were more like “El Tercero”, as the Chronomatics’ Caliber 11 was already being sold under several brands, and unseen but coming up the inside on the rails was a company very far from the Swiss cartels, who had designed and built an automatic chronograph and started manufacturing AND selling it in early 1969: Seiko.

Taking on the Swiss

Founded in late 1800s, “Seiko” was in fact several companies under the family of its founder, K Hattori. As Japan opened up to outside trade and competition, Hattori-san started by importing and selling western clocks, jewellery and watches, before starting to develop its own in-house offerings.

After WWII, Seiko developed a diverse range of horological kit – the official timekeeper of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Japan’s first Automatic watch, its first Chronograph, first diving watch, even getting into high-end accuracy in watches such that they took the fight to the Swiss on their own turf. There were watch “trials” in Neuchâtel and Geneva in the early 60s, to showcase how manufacturers could produce watches of incredible accuracy. After a few misses, Seiko showed up and started wiping the floor – to the point where the highest profile trials were cancelled the year after. Maybe the Swiss didn’t like getting beaten so took their ball away and went home.

Seiko’s “warring factories”

Revisiting the theme of internal competition, one unusual aspect of Seiko’s approach was to have two completely separate factories, separate companies even, operating to win the same customer. Daini Seikosha, in Ginza, downtown Tokyo, and rural Suwa Seikosha, near Nagano, shared hardly any technical know-how and yet were seemingly pitching similar watches to the same customers. The short version of history is that they were out and out competitors, but a subtler take is that both Daini and Suwa were children of the parent, and expected to treat each other with familial respect, even splitting some tasks occasionally.

A somewhat unlikely source, tech company Atlassian hosts a great series of podcasts on telling stories of team working, and they had a really good 30 minute one from the depths of COVID time, on Seiko’s “Duelling Factories”.

It’s never really been satisfactorily explained why Seiko had two factories that shared so little. There are some examples where a watch developed in one was manufactured – perhaps only for a short while – in the other as well (maybe a capacity issue?), but allowing two separate R&D outfits to develop products that directly compete for the same customer seems like madness to most of us. Then again, look at vintage catalogs, and there are hundreds of pages of barely distinguishable watches, so maybe they just threw everything they could at the wall to see what stuck.

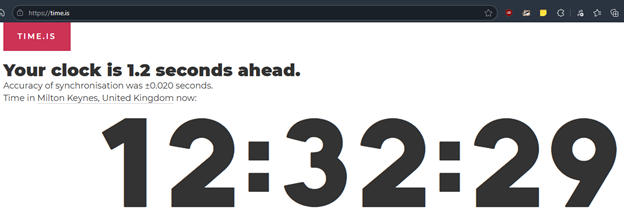

The race for space

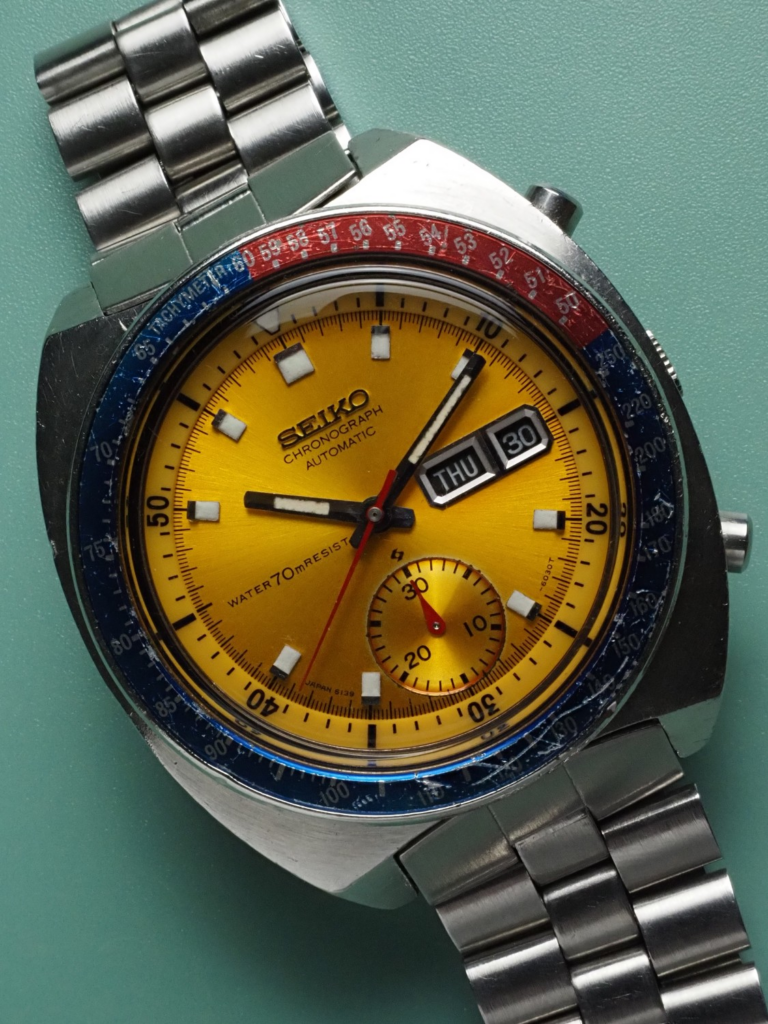

The Suwa factory arguably won the race to make the first automatic chronograph; they had 6139-6010 model watches in production from January 1969. When Jack Heuer, CEO of the eponymous company, was exhibiting their first Caliber 11 watches at the Baselworld show in the spring of 1969, Seiko’s president congratulated him on their achievement, electing not to mention that Seiko had built their own, integrated, in-house automatic chronograph and had been already selling it for months, at a fraction of the price of the Heuers, et al.

The 6139 chronograph went into numerous shaped watches over the decade or so of production, famously adorning the wrists of Bruce Lee, Flash Gordon, even making it as the first automatic chronograph in space via the pocket of Col William Pogue. What later transpired is that Pogue’s mission Commander, Jerry Carr, was sneaking aboard a Movado chronograph too. Movado was a sister brand to Zenith, and its watch ran on Zenith’s 3019 PHC “El Primero” movement. So a dead heat to be the first in zero gravity, then.

In the meantime, the Daini Seikosha factory had been working on its own, thinner and slightly more exotic, automatic chronograph movement – the 7016. Sharing no components whatsoever and being of quite different architecture to the 6139, the 7016 was a few years later to market and arguably missed the buzz of its sibling. As such, 701x watches are a good bit rarer.

Both movements were integrated, i.e. designed from the outset as automatic chronographs, rather than bolted together such as the Chronomatic Cal 11. The 6139 was the first chronograph to use a vertical clutch, an advanced coupling mechanism now the norm for high-end watches from Rolex, Patek Phillippe and so on. The 7016 has a sub-dial register which counts both hours and minutes, has a horizontal clutch but features a flyback mechanism and was the thinnest automatic chronograph movement for 15 years. The more popular square-ish case shape also leads to its nickname, “Monaco”, after the Heuer model.

Maybe they were aimed at the same customer, though the 7016 was around 38% more expensive than an equivalent 6139. Presumably available side-by-side from the same retailer. What were they thinking?