Time is relative, man. In practice, since most of us are not rushing about at or near to the speed of light, it feels pretty much a constant, and is something we all too easily take for granted.

The relative importance of the time of day to a caveman would be what time the sun rises and sets, and he wouldn’t really need to define it empirically since all the other things he interacted with would be driven by the same schedule. He wouldn’t care how many hours there were in the day, only that seasons might change and the days would be longer and shorter.

Measuring time accurately and consistently became a challenge throughout human development, particularly once we started to travel around. Manufacturing, commerce, communications and more all depend on knowing what the time is, sometimes to an extremely accurate degree. Even kiddies’ games too.

Where am I?

In the 17th Century, King Charles II* of England, Scotland and Ireland saw fit to create a Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, in order to keep up with advances in astrology that rivals (especially the French) were making.

Back in 1676, the first “Astronomer Royal”, John Flamsteed, was tasked with finding a way to more accurately navigate at sea. In essence, he began working on the base for subdivision of time zones and for calculating longitude (i.e. how far east or west they are) and therefore help ships not get lost at sea.

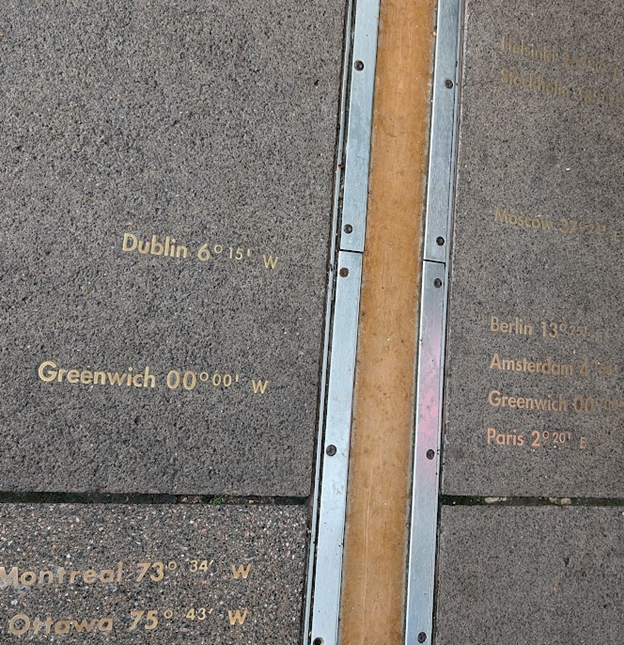

The Prime Meridian was defined quite some years later – 1851 – and was chosen (in 1884) as the basis for most navigation systems and the means by which the globe is split up into time zones. East and West is measured in degrees of longitude with the Meridian (and associated Greenwich Mean Time) at point zero.

You can visit the Greenwich Observatory and stand with one foot in the western hemisphere and the other in the eastern hemisphere.

*Interestingly, while Chaz II was profligate in producing illegitimate children – Irvine Welsh might even describe him as a “flamboyant shagger” – he had no direct heirs. All things being as they are, when current King Charles III’s son, Prince William, ascends to the throne, he’ll be the first monarch descended from Charles II due to his mother’s ancestry.

When is it?

Observing the celestial bodies can help narrow down where you are but to be precise, you need instrumentation which can accurately measure time. In principle, a navigator out at sea could figure out what the time is where s/he was (based on placement of the sun and possibly using stars at night) and could calculate latitude (i.e. how far north or south he or she was).

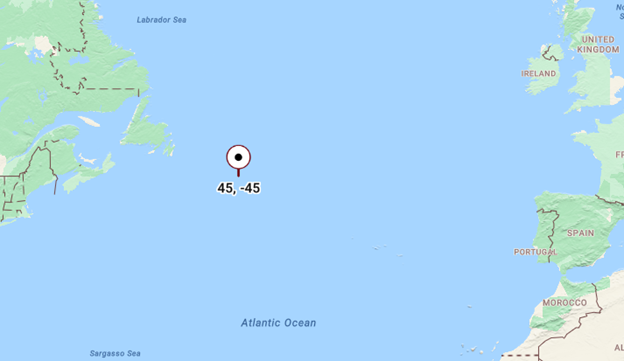

If there was a way of knowing what the time was at a fixed point, then they could figure out longitude as well, by comparing the current location’s time and the what the time was at, say, Greenwich. Imagine a sailor halfway across the Atlantic – if they know it’s noon by observing the sun but they had a clock set to GMT which said it was 3pm, they could calculate the number of degrees of longitude difference and therefore pinpoint where they are, with at least a degree of certainty.

Unfortunately, accuracy of clocks and watches in the 17th century was pretty woeful – many early timepieces only had a single hand, as they weren’t really accurate enough to measure minutes. Sundials remained the most accurate way of measuring time.

The only clocks which could keep good time needed pendulums to swing and that doesn’t really work when the clock is pitching up and down on the waves, so once a sailor had left port there was no way of them keeping track of time at a known point, only the time where they were now.

Following repeated tragic shipwrecks due to vessels being off course to where they expected, the Board of Longitude was established in 1714, with a generous bounty (several £M in today’s money) promised to anyone could solve the problem.

Clockmaker John Harrison devoted much of his life to building clocks and “marine chronometers” which could prove remarkably accurate, enough to measure longitude over a long sea voyage. One test, by King George III no less, measured accuracy within 1/3 of a second per day over a 10-week period, and Captain Cook took a replica of Harrison’s H4 clock to his second voyage down under. They were expensive – about a third the cost of the ship – but if they helped avoid catastrophe, they were worth it. After much shenanigans, Harrison finally received the Board of Longitude’s payout when George III* personally intervened.

*It’s said that when the film version of “The Madness of George III” was released, it was re-titled The Madness of King George, so American audiences wouldn’t think it was a sequel and that they’d missed parts 1 and 2.

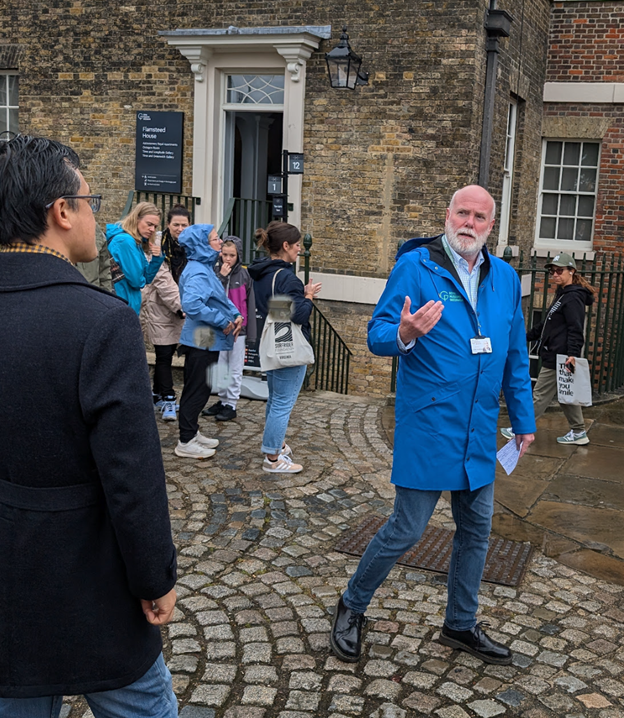

You can take a guided tour of the Observatory, seeing some of Harrison’s clocks and telling the story of what a massive impact solving that tricky problem had, seemingly trivial in today’s world: how knowing the time can help to pinpoint where you are.

You might even be lucky to be guided by former Master Mariner, John Noakes, who now volunteers at the Observatory. A life spent selling strategic software solutions has not dulled his enthusiasm for the subjects of seafaring, navigation and time.

The Royal Observatory played an important part in setting the time for ships, too – at exactly 1pm every day, the brightly-coloured Time Ball drops and any ships within sight of the Observatory could adjust their own clocks to make sure they remained accurate.

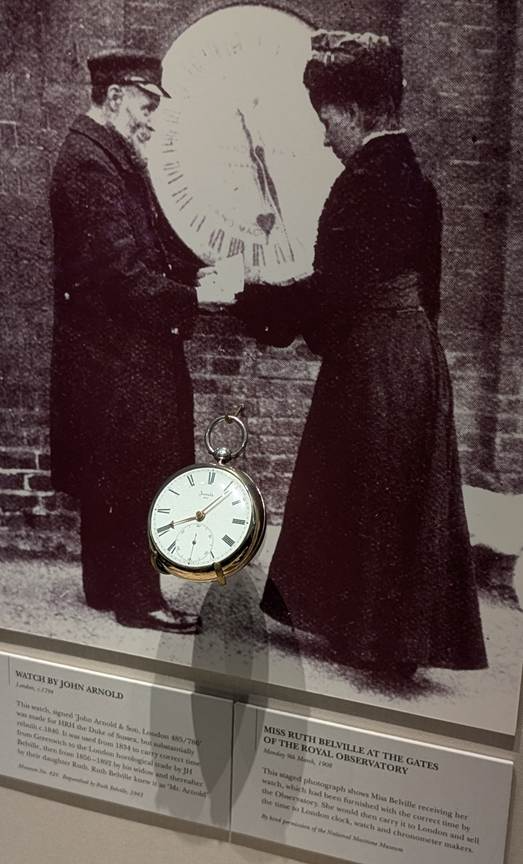

There was even a family – culminating in spinster Ruth Bellville – who “sold time” by taking a 1794 chronometer pocket watch and regularly setting it correctly from Greenwich. First her parents and then Ruth would journey around London, showing the watch to their clients (clock and watch makers, or other businesses) so they could accurately synchronise their own clocks to be within a few seconds of Greenwich Mean Time.

Despite availability of radio technology and even the Pips, it’s pretty remarkable that as late as the 1940s, people were still giving money to an old lady toting around a 130+ year old pocket watch, just to have a look at it.

19th and 20th Century Time

By the early 1800s, it was common for towns in the UK to have clocks in their church or town hall, and that was the reference for things of local importance, like what time the marketplace opened. Those clocks would be set by the midday sun so they would be more-or-less correct.

The problem is, noon in (say) Bristol might be 6 or 7 minutes later by celestial time than it is in London, and that made things difficult when trying to operate between the two, such as making a railway journey according to a published timetable.

Great Western Railway was the first, in 1840, to adopt a universal time standard set by Greenwich, which meant if you were catching a 2pm train in Bristol, it would be 2pm London Time even if a clock in Brissl said it was still 1:53.

Despite some resistance from red-faced locals complaining of interference from the capital city, it wasn’t long before everything across the country became synchronised to GMT and the idea of locally-defined time went away.

From grandfather clocks and pocket watches, by the mid-1900s, wearing a wristwatch became more the norm for gentlemen. Well-to-do ladies may have had a bracelet watch for some time, but it was during the Boer War that soldiers started routinely strapping a small pocket watch to their wrists so they could easily coordinate actions. It didn’t matter so much what the correct time was, so long as they all had their watches synchronised on the same time.

During the mid to late 20th century, the development of electronic time keeping made it much easier for people to know what the accurate time was. Atomic clocks were developed to measure down to tiny fractions of a second, and even redefined the international standard of “a second” as being based on the vibrations of a particular atom.

Scientists have even proved Einstein’s theory of relativity applies, by raising one of two atomic clocks by 1 foot in height, and seeing how it sped up ever so slightly. It’s only 90 billionths of a second faster over the span of a human lifetime, so tall people really needn’t worry about ageing quicker.

Further Watching and Reading

Futurologist Ray Kurzweil proposed in 1999 that the rate of innovation is itself accelerating, so that the first 30 years of the 21st century would see the same or greater technological change than all of the change from the 20th. Some of Ray’s predictions are a bit whacko, but consider that the 20th century itself gave us flight, adoption of mass transit and telecommunications, the transistor, electronic computers, the internet…

… so how have the first 2.5 decades of 21st C gone so far? Smartphones, social media, online shopping, Google Maps, the human genome… Right enough, by 2030, we may yet be supplicant to fuelling the AI overlords.

What’s the time now?

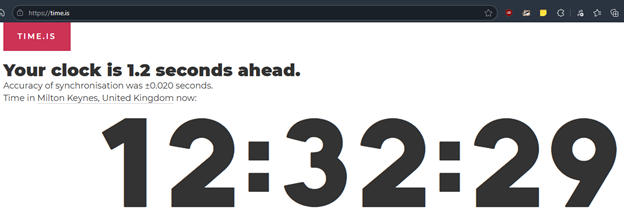

Using your phone or computer, if it keeps its clock set to the network it’s attached to, is probably the most accurate way of telling the time. Try going to the website https://time.is if you want to check how close you are, really.

If you have Amazon Prime, there’s an interesting documentary, The Watchmaker’s Apprentice, which tells the story of George Daniels, arguably the greatest watchmaker of the 20th century, and his protégé Roger W Smith. Daniels is no longer with us, but Smith still hand-makes watches that will routinely sell for >$1M.

If you can get over the somewhat cloying narration of Gimli/Treebeard, it’s quite an good tale.

Morgan Freeman also narrated a series of science documentaries in 10+ years ago, which touched on time, light and space even posing the question of whether time even exists.

There are many time-related stories in Simon Garfield’s excellent Timekeepers book too.

There’s more horological chuntering to follow on Not Tip of the Week, another time…