[Following from part 1, #779: Is the car industry doomed?]

Car manufacturers have been working on the assumption that soon, they will only be selling hybrid and then fully electric vehicles (EVs). Given that the gestation of a new car model is measured in years if not decades, they’ve been pouring $Billions into developing new car designs, new software platforms and new electric drivetrains. They need to skate to where the puck will be, which means there’s a lot at risk if they get assumptions and forecasts wrong.

Initially, some makers offered EVs as an alternative to the pure internal combustion engine (ICE) in existing models – hence you’d see different versions of similar-looking cars being sold, some with just ICE, some with a hybrid of ICE and electric and some with just Battery Electric (BEV). Volvo offered its XC40 in 2021 with 4 different petrol engines, 2 plug-in hybrids, 2 diesels and an EV option. Prices ranged from £25K for the most basic petrol T2 to £60K for range topping electric P8.

Abbreviation soup*

The purest EV/BEV is simply a car that uses one or more electric motors to propel itself. Power probably comes from a large, heavy lithium-ion battery that can take hours to recharge. Public fast-charging stations are springing up but can be complex to install (given the power requirements they need from the grid), and are many times more expensive to use than domestic electricity costs.

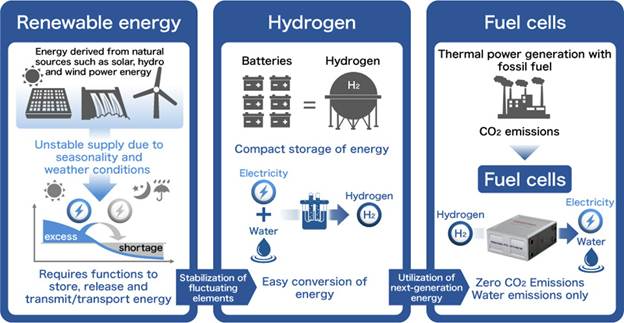

The industry keeps playing with other charging solutions such as swappable battery packs (like old laptops used to offer), or hydrogen fuel cells which generate their own electricity, dispensing with the battery but needing to find ways of getting the notoriously tricksy hydrogen on board.

As technology has matured, existing car companies evolved their ranges by launching new models that were designed specifically as EVs, so could be different to traditional cars in layout.

Mild Hybrids (sometimes known as MHEVs) are easiest to engineer, since they have a small electric motor and battery combination that may just provide additional oomph to the existing ICE, so don’t necessarily have the ability to run on electricity only. They can help the engine be more efficient but don’t replace it in function.

These have been around for years, in various forms – the first outside of Japan was launched 25 years ago, the Honda Insight.

Honda was just showing what was possible if engineers tried really hard to be efficient. Volkswagen did it 10 years later, with the XL1, and various other manufacturers tried, but the most ultra-efficient cars were never really mainstream. Nowadays, Mild Hybrid (or “Self-charging Hybrid” as Toyota calls them) are the easiest way for manufacturers to add some electrification to an existing car platform.

Plug-in Hybrids (PHEVs) try to offer the best of both worlds – a decent sized battery and an electric motor that could drive the car for maybe 50-60 miles, with a reasonable ICE there to provide longer range and more power. On the face of it, PHEVs are the perfect compromise – no real “range anxiety” of needing to charge the car when on longer journeys, while all the pottering about near home or even short commuting can be done like an EV and charged cheaply from home with a plug-in wall charger.

But there are downsides – when the PHEV runs out of electricity, it’s running just like an ICE car, but it’s got a 200kg-ish battery to lug around. When it’s on EV mode, the battery might be a lot smaller than the three-quarter-tonne affair you’d find in a Tesla, but it’s now got the anchor of a passive ICE to make it less efficient, and the motor is probably not as powerful as a pure EV car would have.

Clearly, we have the complexity of both systems to deal with, meaning there’s also more that might one day go wrong.

There’s also a generally unspoken concern about PHEVs – drift up to a roundabout in EV mode and give the accelerator a boot to get in with the flow of traffic, or sweep down a motorway slip-road in EV mode and put your foot down to get up to speed, and you might cause the ICE to fire up and join the party. In principle, that’s great – more ICE power when you need it, and after a while it’ll shut down to let you cruise along in EV mode again.

But what if that ICE hasn’t had the chance to warm itself up yet? If it was a regular car, its oils and seals and things would ideally have been ticking over for a while before being asked to perform at max power.

If the PHEV had been wafting around on electric drive before arrival at that first roundabout, then the driver demands a slug of power that the EV bit can’t deliver, the car is showing the same kind of mechanical sympathy as starting it up from cold and then jumping straight on the power at thousands of RPMs. Sure, the engines should have been designed and lubricated for this mode, to some degree, but who knows what this kind of “duty cycle” will do for long-term reliability.

Finally, there’s another variant that might become more prevalent than PHEVs – the EREV or Extended Range Electric Vehicle. The earliest example was probably the original BMW i3 REX – it’s an electric car but also has a small petrol motor which is used to top up the charge in the battery, giving it additional range. It’s quite possible that more EV makers will start offering this kind of option as a way of dealing with range anxiety. If they’re allowed to.

*Friend of the newsletter Neil Marley eloquently ranted on LinkedIn recently about the distinction between acronym and abbreviation. It would be tempting to say “PHEV” is an acronym, but it’s an abbreviation. Acronyms are new words like “laser” or “radar”; if you have to spell the letters out (like “WFH” or “EV”) then it’s an abbreviation. Capisce?

Driving EV adoption

Leaving aside the truly experimental, the highly compromised early EVs in the modern era were very much the environmentalist’s choice, before Tesla launched the Model S in 2012 and made them arguably as good as existing car options. Most people – though not all – who drive EVs are won over by their smoothness and technology, as well as the feeling they’re helping the planet.

As it happens, the earliest electric cars arguably pre-date the OG petrol vehicle, but lead-acid batteries and later nickel-cadmium rechargeables can’t hold enough juice for any kind of range. It took the development of lithium-ion batteries in the late 20th century to make a mass-market EV practical, banishing the milk float memories of the 1970s.

There’s increasing evidence that EVs can last better than expected, better than petrol or diesel cars. With lower vibration and heat cycles running through the car every time it’s used, and fewer moving oily bits and other parts, there’s less to go wrong, and less that needs servicing. Even the brakes might not wear out as quickly since they’ll use the motors to slow the car down: so-called “regenerative braking” is really just reversing the motor to slow the car through putting drag on the drivetrain, also generating & storing electricity for later use.

Electric car sceptics might say that if the average EV is heavier than an ICE alternative, they’ll potentially wear the roads out more quickly, and though they might not be chucking out CO2 and NOx, they could be throwing tyre particles around in greater volume than lighter cars… though that argument is largely debunked.

Whatever, the industry was at an inflection point a few years ago – when should they stop developing or even stop producing “traditional” cars, and instead put all their efforts into the new technology? Eventually, the price difference between the two might go away but at least in the early days, it was not uncommon for EV versions of an existing car to be significantly more expensive.

Charging challenges

YouTuber Harry Metcalfe has covered a few gremlins with relying on public charging networks; if you can find a charger that works, it takes a long time and isn’t necessarily cheaper than petrol or diesel.

If you could charge your EV at 350kWH and it could cover 3 miles for every kW used, a large 100W battery would still take ~25 minutes to fully charge, and might give you 300 miles of range, at a cost of up to £79 from (for example) GridServe.

Compare that to an average petrol car that could do 36mpg, and you could fill a 55 litre tank in a few minutes, giving you 435 miles of range for about £74.

Right now, EVs only really make sense if you can charge them overnight on a domestic tariff at home – but that can only be for a proportion of the population. And taking a 100kW battery from 10% to 100% charge would take 13 hours and cost (for UK users) about £22, or considerably less if they are on the right power plan.

Maybe the ideal scenario for many households would be to have a larger PHEV or EREV for longer trips or carting the whole family+dog+gear around, and a small 2+2 city car for short haul stuff.

According to the UK government’s Office of National Statistics, the 2021 census gave us some interesting demographic information:

- 23% of UK households have no cars, 41% have a single vehicle and 36% have two or more

- 21% of households live in a flat. maisonette or apartment.

- According to ZapMap, 67% of households have access to a driveway. 9 million households do not, so would need to rely on some kind of public charging network.

- EVA England says that over half of existing EV owners who do not have a driveway rely solely on public charging. 60% of disabled drivers reported issues with accessibility in public chargers.

Is Hydrogen the answer?

Ideally, government should get involved to make sure there’s a sensibly-priced charging infrastructure in place, so people living in cities or blocks of flats don’t get disadvantaged when it comes to using an EV. An alternative might be to invest in having a hydrogen filling network, and then car companies could have a different fuel source for powering their EVs.

Car makers have experimented with Hydrogen as an alternative fuel source for years; a fuel cell car can take hydrogen, combine it with atmospheric oxygen to release electrical power, and produce nothing more than H20. It’s also possible to separate hydrogen from water, though it takes a lot of energy to do so – but large arrays of solar panels in a desert could capture huge amounts of power that would otherwise do nothing and split out hydrogen for onward shipment to where that energy is needed.

The challenge with Hydrogen is that it’s somewhat explosive.

Well, it’s one of the most explosive elements, and can combust at very low concentrations in air. BMW, when making the experimental BMW Hydrogen 7 (which burnt hydrogen in its Internal Combustion Engine rather than using a fuel cell to generate electricity), advised users not to park the car under their house or in fact in an enclosed garage for any amount of time, in case the hydrogen leaked out and blew the whole thing to bits.

While it’s possible to transport hydrogen using variations of the natural gas supply network, it’s not without challenges and speaking with oil & gas safety and risk management specialists, there is little appetite to get involved with it right now. If that could be overcome, a good hydrogen distribution system was established and it became easy to refill your car, then it could provide a useful alternative to the weight and cost of lithium ion batteries and the charging time and range anxieties that negatively impact EV ownership.

A Toyota Mirai hydrogen fuel cell car can add about 5.6kg of hydrogen (at a cost of £10-15 per kg) to its tank in 5 minutes, and that is enough to drive for nearly 850 miles. The Mirai is no featherweight (nearly 2 tonnes) but otherwise is just an electric car in the way it drives, except that it has a compressed tank of gas rather than a big battery. Like Toyota, Honda has been working on hydrogen vehicles for years (including building a joint-venture fuel cell with GM, as used in the hydrogen powered CR-V).

Apart from its tendency for blowing up, the problem with hydrogen for fuelling automobiles is one of the chicken and egg – there are a handful of hydrogen stations in the UK, and the number has been falling, though the UK Gov has put in a bit of funding to add a few more. Without places to fuel up, hydrogen cars are not usable, yet without enough of them to drive demand for a refuelling network, the infrastructure is not viable.

Industrial power

The near-term future for hydrogen power is probably better suited for industrial applications, since the battery electric model is too hard to make work. As it happens, diesel has pretty good energy density – about 100x that of lithium-ion batteries by weight. So, to power an extremely large machine like the Liebherr T284 mining truck (which weighs 242 tonnes dry and has a fuel tank of 5,300L), would need about 500 tonnes of lithium ion batteries.

If you’ve got farm equipment, earth moving machinery or big diggers out in the field, you need them to be running all the time you can – meaning not only would batteries would need to be huge to power those machines on a 12-hour cycle, they would take days and days to recharge.

JCB has been working to build a variant of its diesel engine to run on combusting hydrogen instead. Driving a hydrogen bowser out to the field, connecting it to the fuel tank and filling it up on site makes more sense. Even with the machines burning hydrogen instead of using a fuel cell, it can be a near zero emissions model if the hydrogen was separated using green energy in the first place.

Eco-fuels then?

Another option being pushed by the automotive industry is the use of sustainable fuels. Some mix biofuel with existing fossil fuels to reduce the impact. Some are similar to the hydrogen combustion story with JCB, where if we could manufacture a purely synthetic fuel, then it could arguably be low or even zero emissions in total.

Porsche is investing in “eFuel” which uses hydrogen extracted using renewable energy and combined with atmospheric CO2. When it’s burnt in use later, any CO2 produced is only putting back the CO2 extracted during manufacture.

In motorsport, Goodwood is already using 70% sustainable fuel at the Revival event held in September. Formula 1 aims to be running on 100% sustainable fuel in 2026 – laudable if a little bit greenwashy, given the amount of air travel and freight required to get all their equipment to races…

To some degree, encouraging the continued use of existing fossil-fuelled cars by running them on (more) synthetic fuels is net-better for the environment than replacing everything with EVs. Manufacturing a new EV will add 20-odd tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere – about the same as driving an average petrol car for 100,000 miles.

What does the future hold?

It’s difficult to be sure, but for now the car industry is still backing BEVs as the answer for domestic transportation. Mass transit like buses or for use in industrial settings, hydrogen looks like a much better option if they can deal with the distribution challenge. It seems unlikely that we’ll be running around in hydrogen-powered cars any time soon.

But there are very real charging challenges with BEVs that make it very difficult to imagine 100% usage. Even if pretty much all new cars are BEVs within the next few years, the average age of cars on the road is already growing – up to (in the UK) 9.5 years, up from about 8 before Covid. If you can charge your BEV at home, it’s great – every time you set off, your car is full of fuel. If you can’t charge at home, though, it’s going to be more hassle than if you’d had an equivalent petrol car.

Perhaps PHEVs or EREVs give us the best compromise, especially if they could be run on synthetic fuel. With a 10 year+ lifespan even PHEVs bought now could still be going strong well into the next decade.

The motor industry – especially in Germany, where it’s about 20% of all manufacturing – is lobbying the EU hard to dilute or even remove targets for transitioning to EVs, citing the relative lack of consumer demand and the huge costs they have incurred in engineering as being an existential threat.

Mercedes’ CEO Ola Kallenius recently said, “We need a reality check. Otherwise we are heading at full speed against a wall.”

The closer we get to the end of this decade, the more likely it is that governments will capitulate and extend the potential lifecycle of petrol/electric hybrid cars.

Final part – Government interference in the car industry; rarely a good thing