This is a continuation of an occasional series of articles about how specific capabilities of Exchange 2007 can be mapped to business challenges. The other parts, and other related topics, can be found here.

GOAL: Lower the risk of being non-compliant

Now here’s a can of worms. What is “compliance”?

There are all sorts of industry- or geography-specific rules around both data retention and data destruction, and knowing which ones apply to you and what you should do about them is pretty much a black art for many organisations.

The US Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 came to fruition to make corporate governance and accounting information more robust, in the wake of various financial scandals (such as the collapse of Enron). Although SOX is a piece of US legislation, it applies to not just American companies, but any foreign companies who have a US stock market listing or who are a subsidiary of a US parent.

The Securities Exchange Commission defines a 7-year period for retention of financial information, and for other associated information which forms part of the audit or review of that financial information. Arguably, any email or document which discusses a major issue for the company, even if it doesn’t make specific reference to the impact on corporate finance, could be required to be retained.

These requirements understandably can cause IT managers and CIOs to worry that they might not be compliant with whatever rules they are expected to follow, especially since they vary hugely in different parts of the world, and for any global company, can be highly confusing.

So, for anyone worried about being non-compliant, the first thing they’ll need to do is figure out what it would take for them to be compliant, and how they can measure up to that. This is far from an easy task, and a whole industry has sprung up to try to reassure the frazzled executive that if they buy this product/engage these consultants, then all will be well.

NET: Nobody can sell you out-of-the-box compliance solutions. They will sell you tools which can be used to implement a regime of compliance, but the trick is knowing what that looks like.

Now, Exchange can be used as part of the compliance toolset, and in conjunction with whatever policies and processes the business has in place to ensure appropriate data retention is put in place, and that there is a proper discovery process that can prove that something either exists or does not.

There are a few things to look out for, though…

Keeping “everything” just delays the impact of the problem, doesn’t solve it

I’ve seen so many companies implement archiving solutions where they just keep every document or every email message. I think this is storing up big trouble for the future: it might solve an immediate problem of ticking the box to say everything is archived, but management of that archive is going to become a problem later down the line.

Any reasonable retention policy will specify that documents or other pieces of information of a particular type or topic need to be kept for a period of time. They don’t say that every single piece of paper or electronic information must be kept.

NET: Keep everything you need to keep, and decide (if you can) what is not required to be kept, and throw it away. See a previous post on using Managed Folders & policy to implement this on Exchange.

Knowing where the data is kept is the only way you’ll be able to find it again

It seems obvious, but if you’re going to get to the point where you need to retain information, you’d better know where it’s kept otherwise you’ll never be able to prove that the information was indeed retained (or, sometimes even more importantly, prove that the information doesn’t exist… even if it maybe did at one time).

From an email perspective, this means not keeping data squirreled away on the hard disks of users’ PCs, or in the form of email archives which can only be opened via a laborious and time consuming process.

NET: PST files on users’ PCs or on network shares, are bad news for any compliance regime. See my previous related post on the mailbox quota paradox of thrift.

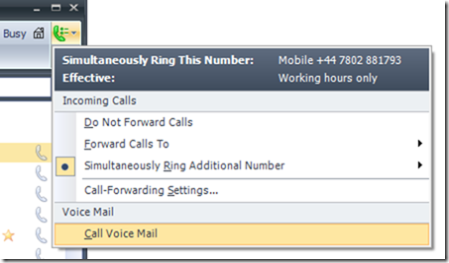

Exchange 2007 introduced a powerful search capability which allows end user to run searches against everything in their mailbox, be it from Outlook or a web client, even a mobile device. The search technology makes it so easy for an individual to find emails and other content, that a lot of people have pretty much stopped filing emails and just let them pile up, knowing they can find the content again, quickly.

The same search technology offers an administrator (and this would likely not be the email admins: more likely a security officer or director of compliance) the ability to search across mailboxes for specific content, carrying out a discovery process.

Outsourcing the problem could be a solution

Here’s something that might be of interest, even if you’re not running Exchange 2007- having someone else store your compliance archive for you. Microsoft’s Exchange Hosted Services came about as part of the company’s acquisition of Frontbridge a few years ago.

Much attention has been paid to the Hosted Filtering service, where all inbound mail for your organisation is delivered first to the EHS datacentre, scanned for potentially malicious content, then the clean stuff delivered down to your own mail systems.

Hosted Archive is a companion technology which runs on top of the filtering: since all inbound (and outbound) email is routed through the EHS datacentre, it’s a good place to keep a long-term archive of it. And if you add journaling into the mix (where every message internal to your Exchange world is also copied up to the EHS datacentre), then you could tick the box of having kept a copy of all your mail, without really having to do much. Once you’ve got the filtering up & running anyway, enabling archiving is a phone call away and all you need to know at your end is how to enable journaling.

NET: Using hosted filtering reduces the risk of inbound malicious email infecting your systems, and of you spreading infected email to other external parties. Hosting your archive in the same place makes a lot of sense, and is a snap to set up.

Exchange 2007 does add a little to this mix though, in the shape of per-user journaling. In this instance, you could decide you don’t need to archive every email from every user, but only certain roles or levels of employee (eg HR and legal departments, plus board members & executives).

Now, using Hosted Archive does go against what I said earlier about keeping everything – except that in this instance, you don’t need to worry about how to do the keeping… that’s someone else’s problem…

Further information on using Exchange in a compliance regime can be seen in a series of video demos, whitepapers and case studies at the Compliance with Exchange 2007 page on Microsoft.com.