The global automotive industry is at a crossroads. Worldwide population growth and demand for cars means some cities are so choked with traffic, you’d be quicker walking. Environmental concerns are driving shifts to electrification while technology intended to improve safety is at risk of distracting and even causing accidents.

Meanwhile, costs have skyrocketed amid worries of slowing consumer demand for brand new cars, leaving industry titans in something of a quandary – they have to invest fortunes to build cars fit for the future. But have they developed vehicles which are too big, heavy and expensive, overburdened with technology that end users don’t want?

What next? Will self-driving autonomous cars become a reality any more than the flying cars vision from the 1950s?

This series looks into some trends, data and perhaps a gaze into the crystal ball on what it all might mean for cars we drive (if we do at all), and the industry which employs 2.6 million people and is valued at $2-3 Trillion annually.

There’s so much to cover, I’ll break it into three parts over the next few weeks.

Part i: “Give the people what they want!”

“Some people say, ‘Give the customers what they want’, but that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do.” — Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs is famously attributed as saying this, even though no definitive source has been found. Jobs supposedly went on to repeat the Henry Ford quote that if he asked people what they wanted, they’d say “a faster horse” (which is almost certainly made up).

Jobs was right, at least when new technology is concerned – show them a Mac when all they’ve used is a command line, or an iPhone when they had a Nokia 2110 and you’ll have them hooked. In the car industry, though, things are a little more complex. One thing’s for sure – if you’d asked people in 1996 what they really want, not many would say “an electric car”.

Changing buying patterns

Rewind a generation or two, and consumer habits for buying cars were radically different than today. Every few years, people would change cars by going to the same dealer they always used and probably bought the same brand they always bought. Loyalty was almost cemented in – you were a Ford family because Dad always bought Fords, or a GM/Open/Vauxhall family as Uncle Ted worked in the nearby factory. Switching car brands would be like changing football team you support.

That started to change when established brands like BMW and Mercedes became more attainable and upwardly aspirational. New entrants came into the market offering arguably superior products, possibly cheaper and/or more reliable. Long warranties tempted people to try out otherwise unproven makes. The biggest shakeup, however, came about due to easy availability of finance.

For years, getting a new car on some kind of PCP deal has been the default (for UK buyers at least) – it’s estimated that ~90% of all new and used car acquisitions are financed, though that may be changing. The premise of PCP is that at the end of the agreement, you could walk away, buy the car outright for an agreed fee or, as happens most often, enter a new PCP for a different car. Historically, this last option has been most likely but is softening as higher interest rates bite and the uncertain future residual value of new cars (especially electric vehicles) puts the costs up more.

More people are leasing or taking a new car on a subscription. City dwellers might rely more on public transport and use Uber or a pay-per-use club like Zipcar. Whatever, the traditional demand and supply models are changing.

Long cycles

Cars take a long time to design and build. From early concepts through to figuring out how they could manufacture and later service the thing, to testing for performance in all climates and crash-worthiness, it takes years and costs millions if not billions of dollars.

Add to that the trend in the last 30 years of “platform sharing” – where a car company will build a modular platform that can be more easily adapted to fit different sizes or types of cars in its own range, or even across brands (looking at you, VW, Audi, SEAT, Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini…). Having to radically update a whole platform let alone the models that it underpins is a very significant undertaking.

Sometimes, car manufacturers try a new model out and it really takes off, so everyone else jumps on the bandwagon. In the 1980s, Chrysler downsized the A-Team sized van to be more of a family run around, and came up with the “minivan” concept, a few months ahead of Renault launching the Espace in Europe. For years, MPVs were wildly popular, before “crossover” vehicles and SUVs started taking over.

Sports Utility Vehicles (SUVs) account for nearly half of all new car sales worldwide and, according to the International Energy Authority, are responsible for a rapid growth in worldwide CO2 emissions. The IEA said if SUVs emissions were measured like a country, they’d be the 5th largest CO2 polluter in the world.

Both MPVs and SUVs are examples of users gravitating towards a new format, compared to their old saloons, hatchbacks, estate cars/station wagons etc. What’s the car industry to do? Make more of those, and less traditional cars, if that’s what people want to buy instead. Volvo recently announced that its XC60 is the most popular model ever, supplanting the iconic boxy 240 estates from the 70s. They’ve been threatening the demise of regular saloon/wagons for a few years.

A handy side-effect for the car makers is that they can jack up not just the ride height, but the margins of these larger cars, and that sometimes means others in their range get dumped due to low demand and/or low profitability. Ford cancelled the Fiesta, a small hatchback that was the best-selling car in the UK for years, for these very reasons.

So, the car industry needs to guess what people want a decade before they’ll be in a position to deliver it. They have to deal with legislature demanding better emissions (hence the journey to EVs) and improving safety.

For the most part, great – cars are way more comfortable and safer now for their occupants (though maybe less so if you’re on the outside; research says that if the US replaced all SUVs with regular-sized cars, 17% fewer pedestrians and cyclists would be killed each year). The trouble is all the extra impact protection, safety systems, airbags, screens, cameras, electric seats, 17-speaker surround sound stereo… they all add weight and cost. Cars are on average around 1/3 heavier now than they were 40 years ago, and there are many which are well over 2 tonnes. The largest electric SUVs are knocking on 3t.

Screens and buttons

As well as changing shape of cars and the way people acquire them, another significant trend over recent years has been the prevalence of in-car tech.

Surveys of intending purchasers shows increasing demand for more safety and comfort systems – in 2023, the top requested thing was a wireless charging pad for your phone but by 2025, it’s more advanced cruise control and automatic-braking protection from reversing into things.

Most cars now offer one or more screens to control in-car systems. Consumers now expect Apple CarPlay or Android Auto on new cars (even on relatively budget-friendly ones), though car makers have been dragged somewhat into making them standard fitment – even a few years ago, Ferrari wanted over $4K as an optional extra to enable the tech, even though it was already fitted in the car and it was just a matter of turning it on.

Other manufacturers have tried monetising enabling features that are there already – as the guts of what the car does are increasingly software controlled, it’s easier to just build all the hardware into every car. BMW floated the idea of users paying monthly subscriptions to use certain features, like heated seats – but rightly got some robust end user feedback that they felt they were being ripped off buying a car with functionality present, then having to pay again to use it.

Other vendors have mooted charging subscriptions for more advanced functionality – like if self-driving becomes a reality, users might be expected to pay per journey to use it. Unsurprisingly, not all users are excited about this business model.

As well as trying to find creative new ways to extract more cash from the end user, car companies have been on a charge to cut costs of manufacture as well – by pushing everything into menus on a screen, they save money from having physical buttons to control stuff like ventilation and heating. They also have a trend for having touch-sensitive “buttons” with haptic feedback, though user feedback is forcing a switch back to actual buttons that enable the user to interact without having to look at the control.

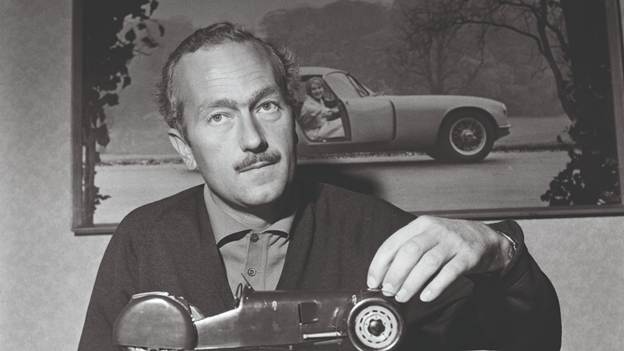

“Simplify, then add lightness”

This quote was attributed – though like all good quotes, it’s difficult to pin down if and when he actually said it – to the mercurial Colin Chapman, boss of Lotus. It’s the distillation of a philosophy that a light car (at least a light racing car) is better. Keeping this simple is also a worthy goal – though in modern cars, it’s more likely that simplicity is a veneer of usability over a hugely complex system underneath. Chapman sailed too close to the wind on occasion when it came to the Lotus racing cars of the 1960s – they were light and simple, but a bit too fragile.

Lightness, however, is a virtuous circle.

In contrast, look what happens when a regular car gets bigger and heavier (because the maker is required to, or if the buyer expects lots of space and bells and whistles inside). It needs a more powerful engine to give it the same relative performance; that in turn might add even more weight and complexity. It will need bigger brakes to stop it, and the wheels will need to be bigger to accommodate them. The tyres will need to be wider to maximise grip, further adding weight and creating more resistance, thus reducing the impact of performance and reducing fuel economy.

This additional “unsprung” weight on each corner makes the car handle less well, so in order to deal with that and all the extra flab onboard, the suspension components need to be thicker and heavier. And so on…

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) face a similar problem – people want a long range (measured in hundreds of miles between charges), meaning they need to fit a large battery (the Tesla Model Y’s battery is apparently over 750kg; that’s more than the total weight of a first generation Lotus Elise).

Because people want big, safe, comfortable vehicles (which are heavier) then either the effective range goes down or the battery size goes up. And when the latter happens, it takes longer to charge the car fully, even if only to cover the same distance. The battery is also the most expensive component in a BEV, so the price rises too. Trying to offset that extra mass by making the rest of the car lighter using exotic materials (carbon fibre and stuff)? Price goes up even more.

What we really need is a small, safe, lightweight (1 tonne), efficient (getting 5miles/kWh) EV with plenty of space inside and a 400-mile range. The downside? If that was possible today, it would cost a million pounds.

Some car companies have tried to make lightweight EVs but with limited success; Honda released the “Honda e” following rave reviews of their 2017 concept car, and it hit the brief – drove really well, not too heavy (around 1,500kgs) and packed full of style and cool tech.

Cool tech does date quickly, though (Top Gear’s Chris Harris once said that buying an electric car is like buying a laptop in the 1990s … you just know that a better, faster, cheaper one will be just around the corner).

Also, small EVs tend to have low range – 100 mile maximum is not bad if you’re shuttling to and from your house and the shops or doing an average commute, but not so good if you have long journeys in mind. Honda dropped the £37K “e” after only 4 years; there are a couple of thousand in the UK so there’s at least some hope that when all that tech starts going flaky in 5-7 years’ time, that parts to repair them might be available.

So, what do we want?

As borne out by survey data, new car buyers increasingly want well-integrated technology in aspirational, safe and usable cars that are environmentally conscious and don’t cost too much. Sadly, these things are not usually complementary. Buyers are increasingly brassed off by massive slab screens in place of any buttons or proper controls, especially in supposed premium cars where the minimalist screen-forward feel looks a bit utilitarian.

The trend for large SUVs in place of regular family cars is getting some lawmakers’ attention too. The joke of the “Chelsea Tractor” is a problem in cities where space is at a premium. Paris tripled parking fees for vehicles weighing over 1.6 tonnes. Some campaigners in London are agitating for similar, and there’s pressure on the UK chancellor to overhaul vehicle taxation away from just emissions-based and focus as well on weight and/or size.

If these measures change what consumers demand from car makers, how long will it take them to design the cars that people want in future..? Is it too late?

Next part – the shift to EVs