This is part 3 of the “Is the car industry doomed?” series, following Part 1 and Part 2.

Looking back through history, government involvement in automobile manufacturing and its supporting infrastructure hasn’t always gone well, though examples do exist of dominant authority proving effective.

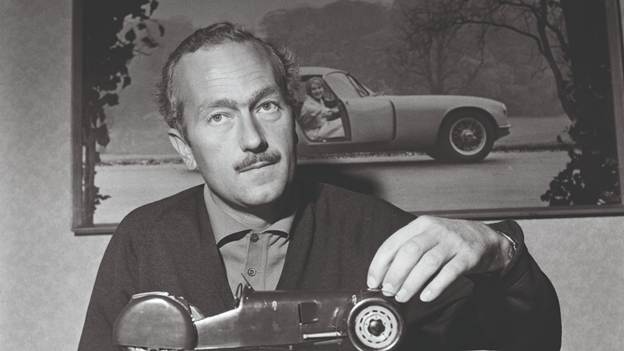

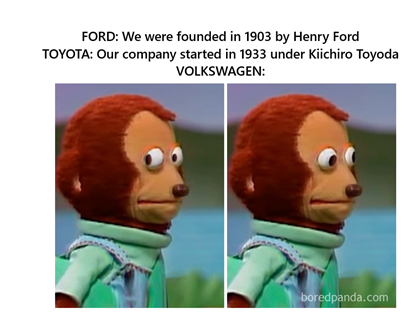

From the mid-1920s, the German government decided it wanted to build a network of roads – which became known as the Autobahn. When Hitler took power, he enthusiastically progressed the project and had the idea in the late 1930s of a car for the masses to go with their new road networks, commissioning a well-regarded engineer called Ferdinand Porsche, to make it a reality.

By the early 1970s, the Volkswagen Type 1 (aka “Beetle”) went on to overtake Henry Ford’s “Model T” as the most produced car up to that point, eventually tapping out at 21.5M models over an unbelievable 65-year lifespan. It was eventually overtaken by the Toyota Corolla, which remains at the top with over 47.5M produced in nearly 60 years.

The British Leyland experiment

In 1968, numerous established British car brands merged with the goal of being able to take on the globalising American juggernauts like Ford and General Motors, through creating efficiencies, economy of scale and all that kind of stuff.

Sadly, it didn’t go too well and the UK Government had to step in and nationalise the whole thing in 1975, under the “British Leyland” name.

There followed years of industrial turmoil, cars that were less well built or less well received than expected, and eventual dismemberment and sale of key brands like Jaguar and Rover. Government interference may have partly caused the merger to happen in the first place. Eventually it had to get involved in running a business it knew nothing about, in order to save face and thousands of jobs.

Zero Emissions Mandates

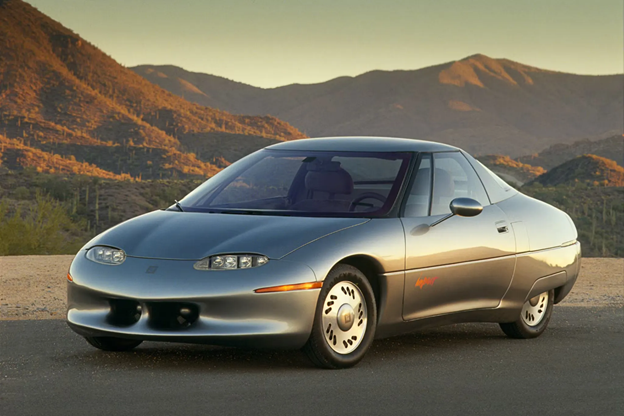

Coming back to the present day, before Covid, legislators in the EU (and the UK, which was still part of it at the time) decided that in order to reduce emissions and enthusiastically champion the kind of growth that Tesla was starting to experience in the US, they should encourage the car industry to invest in a transformation to electrification.

So, governments started offering incentives to offset the additional costs for end users, through direct subsidy to consumers, grants for installing home-chargers and tax breaks for companies supplying EVs to their staff. They also invested in improving public charging networks and ultimately legislated to force car companies to reduce emissions and speed up the uptake of EVs.

The US government never compelled an EV shift (though the law on trying to reduce pollution from gas guzzling vehicles was often mis-appropriated as an “EV Mandate”).

The European Union, however, did set out rules that meant it would no longer allow the sale of petrol or diesel cars after 2035, with stringent targets to reduce emissions of Internal Combustion Engine cars ahead of then. The EU threatens to penalise car companies based on the average CO2 emissions of their sales – though a reprieve has been granted for now.

Car companies reportedly considered restricting the numbers of its most polluting models, dropping certain ICE configurations altogether to avoid selling too many (and racking up fines by the resultant raising of their average CO2 output). In some ways this is what the legislators want, even if that means the highest performance cars in the range (such as Porsche’s 911 GT3) have to be restricted in numbers, even if the demand is there to sell more of them.

The UK government in 2020 decided that they would accelerate the move to EVs, and ICE vehicles would be phased out by 2030. That has now been relaxed to keep in step with the EU, given than the global car industry would be targeting the 2035 date for compliance anyway.

The current US administration quickly tore up the environmental restrictions due to take effect from 2027, so for now it’s perfectly OK to keep on buying the mix of pickups and SUVs that seem so popular.

The best selling “car” in the US is the Ford F-150, which will do about 14-17mpg in real world driving, emitting around 250 – 350g/km of CO2 (in the European model) depending on engine size.

The top selling car in the EU, by contrast, is the ICE-only Dacia Sandero, which will get 53 miles per UK gallon, emitting only 119g/km of CO2. [Note that the UK gallon is about 20% larger than the US one, so if the F-150 could do 15mpg in the US, it would be more like 18mpg in the UK].

Do Consumers want them, though?

Forecast demand for EVs is picking up but it’s still a long way from being the dominant form of propulsion. They are often more expensive to buy than traditional ICE cars, even if the running costs over time might be lower. Residual values have so far been poor – headlines saying that EVs lose half their value in 2 years could be enough to give buyers the jitters about buying a new, premium electric car.

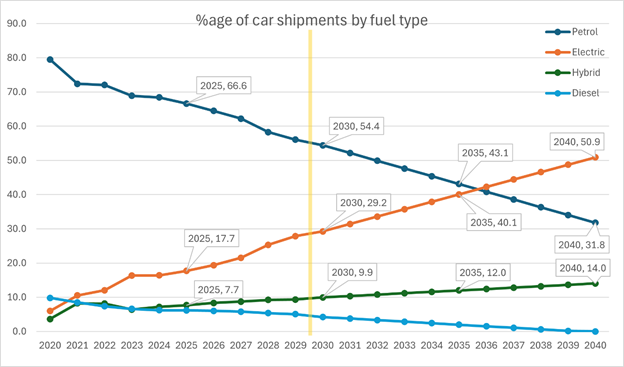

Analyst Statista provides data with forecasting until 2029; taking a straight-line extrapolation (which is unrealistic but serves a purpose) from 2030 to 2040, would conclude that even by 2035, Petrol shipments would still have the upper hand.

Data Source: Automotive industry worldwide – statistics & facts | Statista up to 2029, then a straight-line extrapolation from 2030 – 2040.

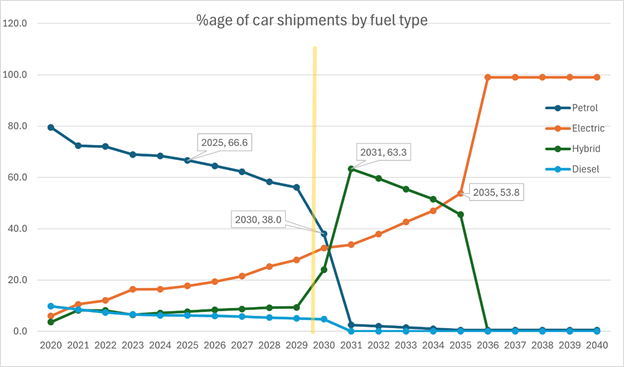

If government mandates and incentives keep being offered or even increased, it’s likely that EV uptake will accelerate. If we assume that pure petrol and diesel will to all intents dry up post-2030, and that there’s at least a bump in hybrids for a while before them being essentially unavailable after 2035, maybe it would look like …

Data Source: Automotive industry worldwide – statistics & facts | Statista up to 2029, then an estimate of decline in petrol/diesel and stronger uptake of EV and (to 2035), hybrid

In truth, it’s unlikely that diesel, petrol or hybrid will completely stop in 2030/35. Even if the EU keeps its restrictions in place, there’s no telling what the US might do, or what will happen outside of these major blocs. We’d assume that pretty much all petrol and diesel will become MHEV or PHEVs, and for a while at least would continue to out-sell EVs.

Some car manufacturers bet the farm on EVs – take, for example, Geely. Amongst various Chinese domestic brands, they own Sweden’s Volvo & Polestar, the London taxi company and former UK sports car maker Lotus. Polestar used to be a sporty sub-brand for Volvos, like Mercedes’ AMG or BMW’s M-division, but it spun out as a separate company initially offering a high spec PHEV before launching a range of BEVs.

Polestar is reportedly circling the drain, with $1Bn losses and middling sales figures, though their boss said they’re going to stick it out. They have launched several new cars in the last couple of years and it’s taking time for them to gain traction while the 5-year old Polestar 2 is looking less competitive.

Volvo’s pure EV sales are down YoY by nearly 25% and sales across the board are falling. Lotus tried to do a Porsche-style pivot (diversifying from just doing sports cars to more lucrative SUVs) by launching massive Chinese-built EV cars, but is both rowing back its pledge to move to EV-only for its UK-built sports cars, and is even looking to add a turbo-petrol “range extender” engine to it EVs to effectively make them EREVs. The Lotus Eletre SUV, designed and built by Geely in Wuhan, is expensive and heavy enough, and not particularly efficient. Wherever they could fit a petrol engine will only make it even more compromised.

Even with government assistance and tax penalties on more polluting cars, it seems people aren’t rushing to spend £100K+ on a 2.5 tonne luxury electric SUV. Lotus also joined the breathless pre-COVID rush for EV hypercars that would produce crazy power and cost millions of pounds. It seems the uber-rich don’t much want them either.

Complexity and Usability

As well as concerns about how they’re powered, consumers might be cooling on buying new cars in general. What with [waves arms around above head] “all of this”, keeping older cars running make more financial sense for many.

For driving enthusiasts, even buying new ICE cars – in Europe at least – also comes with the downside of a variety of mandatory safety features. On the face of it, more safety = better, but the new GSR2 regs require a variety of systems (like speed warnings) to be enabled every time you start the car, which means the car beeps and bongs for a variety of reasons, and can take many menu options to deselect the features.

Ironically, with the trend to replacing physical buttons with screens, the driver-monitoring camera on a modern car will tell you off for not keeping your eyes on the road, just because you’re trying to change the cabin temperature on the big screen whilst moving.

Car journalists talk about “peak car” being 8 – 12 years ago; stuff that has come out since is often more complicated, more expensive and not as nice to drive, even if they’re supposedly safer and better for the environment.

Will legislators blink?

It remains to be seen whether the powers-that-be will continue to try and make the industry switch fully to EVs. The use of tariffs by the Trump administration might stymie imports from overseas, but there’s little incentive for domestic US automakers to fully embrace EVs or even make their existing gas guzzlers super-efficient – Tesla being the notable exception. At least for now, tariffs are also restricting some cars from being sold in the US, as they’d just be too expensive – Volvo’s new Chinese-built ES90 “saloon” being one example.

In the early 2000s, the UK government (among others) incentivised diesel cars as a more efficient and less polluting (from a CO2 perspective) alternative. Fast forward a few years, and diesel particulate and NOx emissions were recognised as being a health danger and the naughty car companies were cooking the books (“Dieselgate”) when it came to emissions testing. It’s just over 10 years since the United States EPA raised its concerns about emissions not being reported correctly.

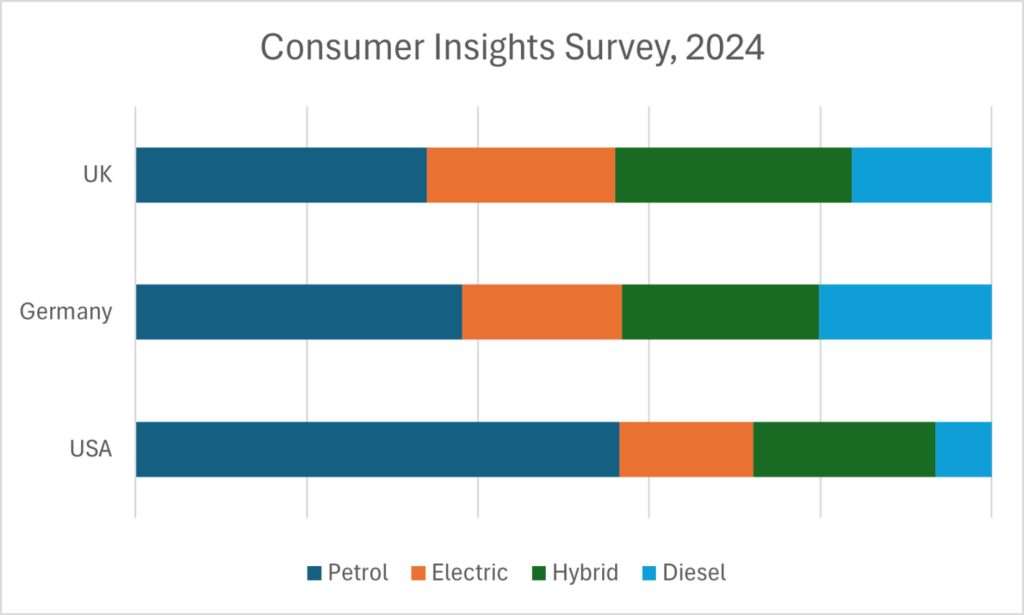

According to the Consumer Insights Global Survey, when asked in 2024, US buyers were 69% looking at Gasoline/Petrol, 19% Electric and 26% Hybrid, with Diesel accounting for only 8% (clearly, each consumer might be considering multiple options since the numbers don’t add up to 100%…)

Germany looked a little more positive, with 53% evaluating Petrol, 26% Electric and 32% Hybrid (though a stalwart 28% still want Diesel, it seems). The UK was 48% Petrol, 31% Electric, 39% Hybrid and still 23% Diesel.

Even a decade before we’re expected to switch to EVs, with these patterns in consumer demand, it feels like we’re going to get a lot of hybrids before we go fully electric, if that indeed happens.

The threat from China

The Chinese market has evolved over the last 25 years; at one point, it was the new nirvana for Western brands as newly affluent Chinese consumers wanted to snap up luxury products from Europe and the US. Auto makers rushed to set up manufacturing facilities in China to serve the growing local market, even producing specific models (like Audi launching the A6L long wheelbase for people to be driven around in).

That is now changing – the overall luxury goods market in 2025 is estimated to grow less than 1% in China, compared to 1.2% for North America and 2.4% for Northern Europe. While still expanding, the Chinese economy growth rate is slowing and consumers are turning more to cheaper, local brands.

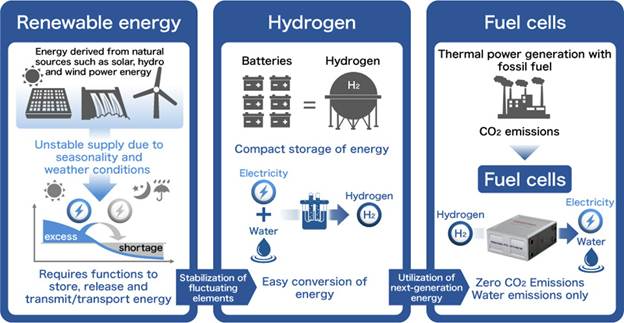

At the same time, the Chinese government’s long-term investment program in the infrastructure and manufacturing capability for electric vehicles started to pay off. Now, the list of best-selling electric cars is dominated by Chinese manufacturers.

If the world’s car market is pivoting to be largely if not entirely electric, then BYD and similar brands could be the dominant maker of EVs, even if they have to spin up factories in other parts of the world to sidestep tariffs and other blockers.

Even though the charging networks are more advanced in China than in many other parts of the world, consumers are still worried about range and charging times. This has led to the development of waves of “NEV” – New Energy Vehicles – which are fundamentally electric but not exclusively so. Petrol-powered EREV – range extender EVs – are gaining ground and may become the default since they appear to offer all the benefits of EVs but can run for hundreds of miles.

If Europe and the US are going to still have an automobile industry in 10 or 20 years, they will need to compete with imports from China that are potentially much cheaper, and due to experience and scale, will probably be better than the ones coming from established western auto makers.

So, is the car industry doomed?

Well, obviously not entirely – but the constituent parts of it in a decade or two might be very different to what we’ve got used to over the last 30 or so years. German hegemony at the premium end of the market is certainly looking under threat.

- BMW led with innovative electric offerings in the i3 and i8 of 2013/4 but fairly quickly realised they were not going to have true mass-market appeal. It’s taken them years to evolve the rest of the range to offer competitive BEV offerings, but they are now leading the field in Europe (even before Tesla’s sales were negatively affected by it’s CEO’s behaviour).

- VW/Audi have had a difficult time, too – early software problems and a poor UX left mainstream buyers waiting (maybe the old adage of not buying anything from Microsoft until v3 also applies here), and they might have struck the crossbar above the open goal of the appeal of an electric Golf replacement when the ID.3 was first launched.

- Mercedes, despite having some remarkable technology, have struggled to build and sell something that buyers want. Their boss has even warned of an existential threat to the entire industry if the lawmakers continue to enforce adoption of EVs too quickly.

So far, the Chinese manufacturers are grabbing market share by selling good-enough BEVs at a price that beats the premium offerings from Germany, and undercuts the alternatives from US, Japan and Korea. Renault has scored a hit with its cutesy R5 so there is hope from within the established industry that they can make a product that buyers want.

Time will tell if that’s enough to save the existing car makers or if they’ll be replaced by a new wave of names from China and elsewhere.