Firstly – this is not “Tip of the Week”, it’s “Not Tip of the Week” since it isn’t Weekly any more. I have picked up from the last ever Tip of the Week and decided to carry on with its numbering. The goal is to do something occasionally, maybe monthly, and it will probably be longer form.

Analogies abound for scenarios where someone has a solution to a problem that was not necessarily foreseen because they looked at it from a different perspective.

A great one was coined by ex-colleague Darren Strange, when thinking about how smart people often approach a set of targets. As well as setting the goals, the authorities will lay down a set of rules by which they expect everyone to operate. Sometimes, playing fair and within the technicalities of the rules can yield bountiful results. Darren likened these clever people to the velociraptors in Jurassic Park – systematically attacking the electric fences designed to contain them, in order to find and exploit any weaknesses.

We should celebrate the velociraptors in our lives and find ways to think like they do. Without the killing and eating people bit. Obviously.

Making the <…> go faster

Some of the best examples of genuine innovating thinking is when coaches look to improve performance by focussing on making the environment better, or engineers are given a set of regulations and they come up with ways to “beat” the rules by using a new approach.

It could be a fanatical focus on the end goal (see Ben Hunt Davis’ “Will it Make the Boat Go Faster?”), or Dave Brailsford’s legendary “marginal gains” approach where a 1% improvement in every aspect compounds to make giant leaps in results. In some sports, innovators or engineers might concentrate on shaving off every gram of weight, such as was famously done in cycling by the legendary Eddy “The Cannibal” Merckx milling and drilling bike components to lighten them…

Motor racing is similarly obsessed with weight and performance, where millions of dollars could be spent chasing a fraction of a second per lap speed improvement.

The Professor

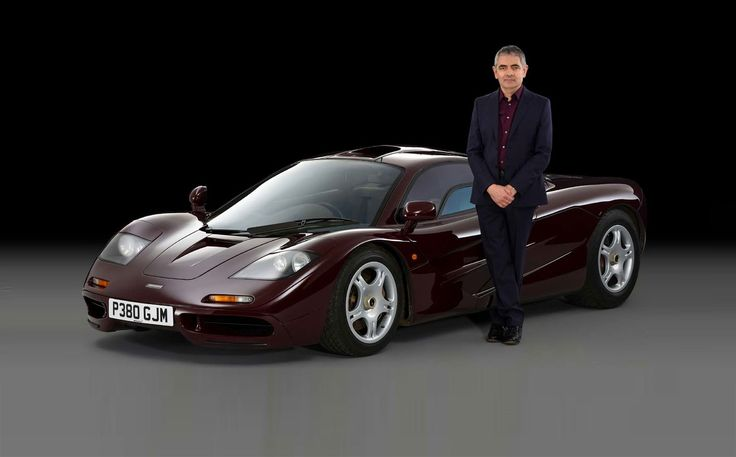

Talking of things automotive, one legendary velociraptor is celebrating 60 years in the industry this year: Professor Gordon Murray CBE. He was celebrated at Goodwood FoS and has appeared in various magazine specials. If you haven’t come across the Prof’s work, it tells a story of someone not like most of us.

Arguably most famous for one of the most impressive cars ever made, explicitly designed NOT to be a racing car yet almost forced by their customers to develop it for competition… and when they did, it won the hardest race in the world (The 24 hours of Le Mans) at its first attempt: the McLaren F1.

The Greatest Car … in the World

Top Gear’s Tiffany Dell reviewed it at length in 1992, and again 10 years later. Everyone, it seems, loved it.

Well-known owners included Rowan Atkinson, who famously pranged his car leading to the largest ever car insurance claim in the UK at the time (costing nearly £1M). A certain Mr Musk got his in 1999 and binned it (while uninsured) a year later, showing off to Peter Thiel (apparently, he said “Watch this!” and then went straight to the scene of the accident).

You might think famous people have a bit of a habit of crashing F1s – Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason, custodian of the very first F1 GTR racing car came a cropper somewhat publicly in a track parade at Goodwood.

The F1 was unique and ground-breaking in so many ways, largely because Murray assumed the brief of making the best car in the world, bar none, whatever it cost. The driver sat in the middle because that was better. It was made of motorsport-grade materials so despite developing incredible amounts of power (627hp), it weighed not much more than a ton and was the fastest road car in the world for decades. Even the engine bay was lined in gold leaf because it was better at heat management.

At the time, the F1 was rare and arguably a commercial flop – it was £540,000 +tax when new, which in 1992 was a lot. That’s about £1.2M in today’s money, but one of the 64 road cars that were made would probably cost you £15M to buy today, if not more.

The Other F1

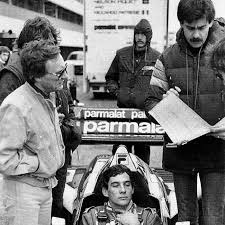

Gordon had cut his teeth in the Formula 1 industry, becoming the chief designer at the underdog Brabham team at only 26, promoted by its then new owner, Bernie Ecclestone.

Gordon went on to great things with Brabham and later onto McLaren, where his cars won ¾ of the races they entered. Bored with achieving everything, he went on to develop the F1 road car and has had some other notable successes more recently.

The Pit Stop

But one of Murray’s innovations from a decade before the F1 went on to have a seismic effect on the whole of Formula 1, and it was largely because he thought of something that hadn’t occurred to anyone else: using pit stops strategically rather than when something went wrong.

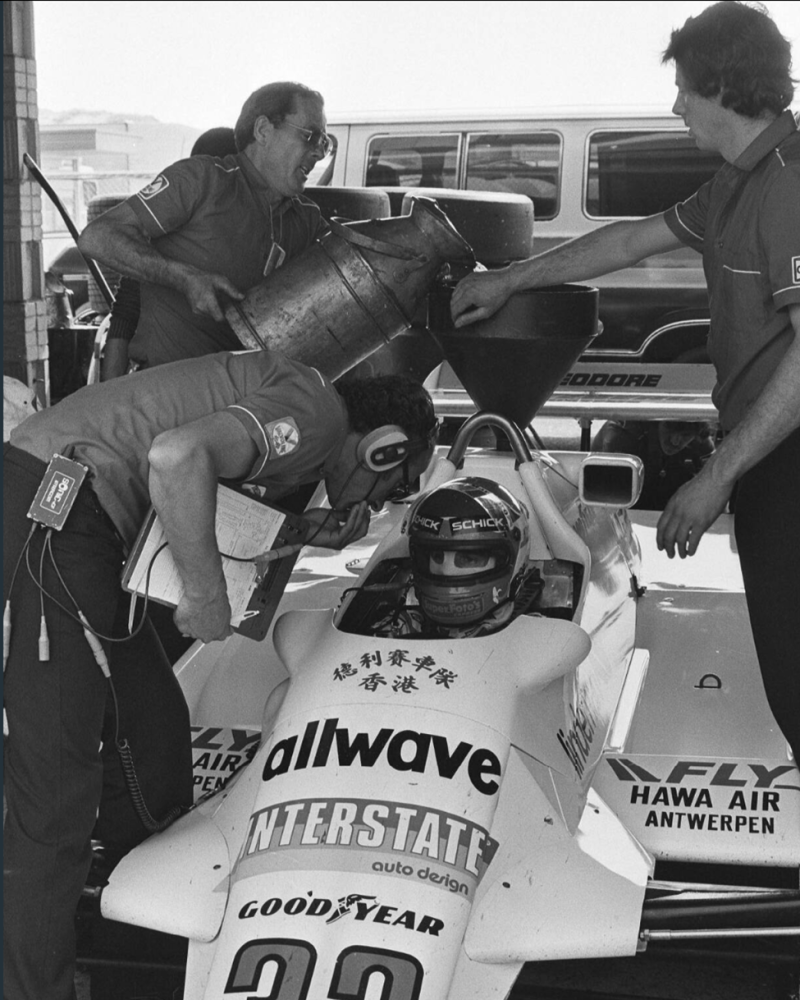

In recent years up to that point, when a car stopped in the pits it was because of a puncture or some other problem, which could take minutes to fix. Wheels were attached with nuts and wrenches, and coming into the pits was a surefire way of losing the race.

Some engines, like the new BMW turbo unit that Brabham was using in 1982, were especially thirsty and comparatively heavy, compounded by needing to carry the whole fuel load from the start. At that point, if cars needed fuelling during qualifying or testing it was slow and alarmingly basic – literally pouring fuel in from “milk churns”.

From the Dutch National Archives – http://hdl.handle.net/10648/ad1a9284-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84

During the 1982 season, Murray’s team came up with an array of kit that nobody else had thought of – pressurised refuelling rigs made from beer barrels that could pump a whole family car quantity of fuel into a racing car in a few seconds. Wheel fixings and compressed air guns that could remove and replace a wheel in a fraction of the time it would have taken with spanners and brute force.

As well as being weighed down at the start of a race with a full tank of fuel, the cars only used one set of tyres during the race. Murray calculated that a car with less fuel (ergo, less weight) would be faster from the outset and its tyres would take less punishment. Also, by the time everyone else was lightened through having burned most of their fuel towards the end of the race, their tyres were worn out.

If the Brabham could pit half or even two-thirds of the way through the race and get nice new boots, they would be 2 or 3 seconds a lap quicker than everyone else. Doing the numbers meant that even if they lost 30 or 40 seconds bringing the car into the pits to add fuel and change wheels, they would make the time up by being faster all the rest of the time.

One problem was that when new tyres and wheels were fitted during the race, they would be stone cold and would take a few laps to get up to temperature and produce enough grip. The solution was to design plywood-carcassed, gas-fired “warming cupboards” that could keep a set of tyres nice and toasty.

The team tried it (not very successfully) from halfway through the 1982 season; their car was so unreliable that it barely ever made it far enough into the race to need a strategic stop.

Murray expected that everyone else would do the sums and turn up with the same technique the following year, but they didn’t. Not only that, but he designed the 1983 car specifically with refuelling and pit stops in mind (for instance, it had a smaller fuel tank) and with BMW fixing the engine reliability issues, they were much more competitive. Nelson Piquet went on to win the driver’s championship with Brabham, and the team came third in the constructors’.

Red Bull TV produced a great documentary in 2016 charting the development of the pit stop, and celebrating the modern efforts to reduce the time taken to replace all 4 wheels on a modern car – McLaren currently holding the record at a scarcely believable 1.80s.

Watch on Red Bull TV’s website – The History of the Pit Stop | How it came to F1. Red Bull TV also has apps for various Smart TVs; there’s also an unauthorised rip of it on YouTube, along with expanded interviews with Gordon Murray on the subject.

Read the rulebook, rewrite the rules

This out of the box thinking exemplified by Gordon Murray came because (he said) he read the rules cover to cover and inside out. He saw what the constraints were in his field of operation, and figured out how to do things that nobody else had thought of. Instead of looking at the rules as defining what he could do, he adopted the approach of finding things (within reason) that the rules did not say he couldn’t (see also the earlier Brabham “Fan Car”).

Even though the F1 authorities banned refuelling the following year, when they reintroduced it – in a more controlled, regulated fashion – in 1994, then the fuel and tyre strategy of every team became an intrinsic part of their race plans. Pit stop strategies can still decide race wins today (see Max Verstappen somewhat controversially winning his first drivers title in 2021, since he was on fresh tyres and his rival Lewis Hamilton was not).

The great velociraptor Gordon Murray and his team revolutionised the sport by thinking like nobody else.